The Burden of Memory

photography by John Trotter

Interview by Veronica Gorodetskaya

In 1997, photojournalist John Trotter was on assignment taking photographs for a local Sacramento newspaper when he was brutally attacked and beaten. The assailants demanded his film but, for whatever reason, did not remove it from his camera.

Days later, John woke up at Sierra Gates, a brain injury rehabilitation facility located in the Sierra Nevada foothills above Sacramento. He remembered nothing of the attack.

His brain injury affected his short term memory, which made everyday activities like going to the grocery store both difficult and disorienting.

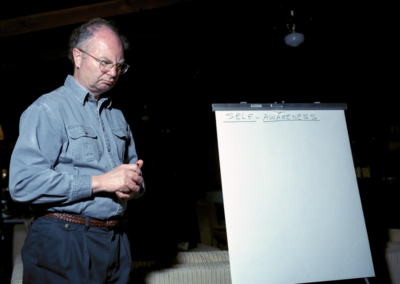

Eventually, at the urging of his speech therapist, John picked up the camera again. After his release, he went back to Sierra Gates to photograph fellow brain injury patients and their staff over several years.

What started as an exercise in recovery and rehabilitation, developed into a lifelong exploration of how the camera can mediate the aftereffects of trauma and its impact on memory.

The camera relieves us of the burden of memory. It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other god has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.

John Berger

Who has influenced you—writers, photographers, or artists—in the understanding of trauma and memory?

I had read John Berger at that point. He wasn’t necessarily writing about trauma but—

About perception.

So much about perception. It’s funny because I came to his writing, even as a photographer, through his novel, Into their Labours, which is part of a trilogy about the end of peasant life in Europe. Outside of John Berger, I read Wendell Berry, who’s an American writer that advocates a more simple and rural existence. He talks about our whole disconnection from life. According to him, many problems in the world can be traced to the degree of disconnection of people from the production of their own food. I was looking to find how you become reconnected to your own life.

Because you were feeling so disconnected from it?

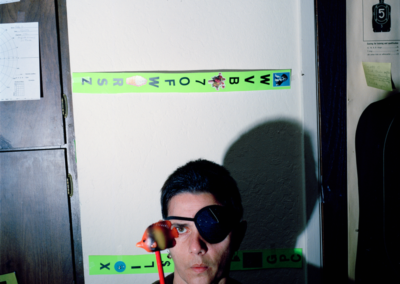

Yeah, I had changed. I was, and still am, overwhelmed by too many stimuli coming at me. There was a point early on when I’d be talking to someone, and if there was some background noise or light, I’d shade my eyes with my hand to make the stimuli go away so I could process it with my brain. It’s the craziest feeling to find yourself like this. I was somebody who never got involved in drugs. I never drank to excess. People have experiences with drugs that alter how they experience all the stimuli that we have coming at us. I didn’t have that, and even then, the drugs last only until they wear off—but this was a permanent condition.

Would you say that it changed you as a photographer?

Yeah, it did. I sort of had a way of working that I was comfortable with. I mean, I wasn’t really, in the end, a newspaper photographer. I was—I worked as one, but…In newspapers, at the time, it was kind of scary to imply that there was anything else other than what you saw right there on the surface. I think there is a lot of that in America. The photography that I have been drawn to, and then tried to make for myself, is about trying to be aware and to communicate about the inner life that is going on in the people that you see in the photographs.

And the work that you did at Sierra Gates brought you to this understanding?

I’ve always tried to do that, but I didn’t quite understand it. Once I was let out of Sierra Gates, about two and a half months after I was admitted, the speech therapist I was seeing as a day client said, I’d like for you to start taking pictures again. Would you like to do that? And I said, ok. She asked what I’d like to photograph. I thought about it.

I wanted to photograph at Sierra Gates. It felt safe. Almost no one–even at the newspaper–knew where I was. I felt like I could not move forward in my life until this whole criminal justice thing played itself out. At this point, law enforcement had arrested one of my attackers. The best anyone has been able to tell is that there were six of them. I was terrified of the idea of photographing in public again. It’s also the first place I remember from this new life I was in. It felt like a good place to start.

I started photographing to try to understand what had happened. My experience as a photojournalist was that you, the photographer, and the people in the photographs are not the same—there is a difference. But after a year of doing this, I finally had to acknowledge I was really photographing my own experience. I wanted to photograph how I felt. At the same time, I was photographing the experience of the people in the photographs, an experience that I think I understood pretty well.

You said you wanted to understand how you felt. How did photographing and spending time with fellow patients help you process your own trauma?

That hadn’t occurred to me. I was just thinking in terms of taking a series of self-referential portraits. Looking back now, I wish I had taken more of them, but I didn’t think I could’ve done it in any kind of revelatory way. I guess a part of it was to reconnect with the photographer I had been because that was part of everything, trying to reconnect with life. I am a photographer, and I learned how to be a photographer again by doing this.

So that photographer’s instinct was still there?

I was afraid of it at the same time—I had been attacked because I was a photographer. Whatever I had done as a photographer was threatening enough to these people that they were ready to kill me for it. So, while they may have been this natural inclination to look at the world that way and to photograph that world, I was also terrified of the idea of photographing again. I could never photograph in public, especially considering all this time these juveniles were just walking around. As I’ve said to people, I could be riding the same elevator and with them, and I wouldn’t have recognized them.

On the one hand, you are trying to work through all of this; at the same time, your hands are tied because you can’t quite contribute to a sense of justice for yourself. You can’t say, yes, I recognize this person because there is no memory of it.

Yeah, there it is—that’s the burden of memory. And when I was reading John Berger’s book About Looking the quote, “The camera relieves us of the burden of memory. It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us” jumped out. The burden of memory had so much to do with what had happened to my everyday experience—the short-term memory.

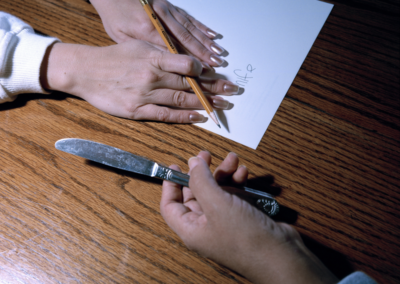

I can give you an example of someone I photographed, this guy Kent, who had had an aneurysm. He wasn’t able to do therapy because he’d be extremely agitated, telling people, look, I have an important phone call I need to make to my wife. And the staff would say, Kent, you just talked to her five minutes ago. But he had no memory of it—none—as if it had never happened. So, how do you have a life? My short-term memory issues were not as profound, but I could understand in a way I could never have before.

Running parallel to the function of memory in everyday life is the whole justice system part. Everything about that is about establishing what happened—memory—the chain of events that establish the facts of how a crime was committed or not. It’s based on witnesses and their own recollection and perspective of events. And so, in a sense, justice is so much about memory—establishing what happened.

I remember having a conversation with a guy who’d also had an aneurysm, and he said: it’s just like right now, talking to you, there is this point when you are having a dream, and then you segue into being awake and the line between the two is no longer clear. Am I having a dream when I am talking to you, or is this the real thing? He kind of laughed about it, hey, this is my life.

For me, it was a little bit like that. I would think, was I out here earlier this week, or was it something I had a dream about? But then I would go to the processor, pick up the film with my hand, look at the plastic strips with emulsion on them that had been processed, and there were these images; it wasn’t a dream. I had been out there watching somebody go through this therapy.

Photography relieved me of the burden of memory I was carrying at the time; what I could and couldn’t remember; whether they’ll be able to convict these guys. It felt like so much was on my shoulders because so many people were just not going to allow their memories to be accessed as witnesses.

In the end, a little girl named all the names. That’s how they made all the arrests. She was eight years old, and the neighborhood basically put it on her shoulders. When they tried to put her on the stand during the trials, she just fell apart. It was too traumatic.

And you, of all people, understand her burden remembering these events.

She, in a sense, was carrying the trauma of what had happened to me. She saw it, she remembered. According to the cops, she was describing blow by blow; who did what, how many times. It was stuck in her head.

The double-edged sword is that I don’t have to live with the absolute memory—blow by blow—of what happened to me, unlike a lot of people who have experienced trauma. At the same time, a part of you thinks that there is an evolutionary process of preventing future trauma by understanding what happened and avoiding certain things. Learning. I had to understand what had happened from other people.

There was some much related to this photographically. These guys didn’t take my film, and so the film in my camera got processed, and the newspaper gave it to the cops as evidence. And here was this record of people I had encountered up until that point, which at the time, unlike now when there is electronic surveillance all around us, all the time, was kind of unusual.

Nowadays, you could go around the neighborhood and find a camera up on a power pole somewhere recording all the activity below it. And here there was on film the people I had talked to. The attack wasn’t on film, but again there is photography and memory, and the meaning of photography has changed in the years since then because everyone has cameras with them all the time on their phones.

We wondered about the relationship between technology and memory. If we want to remember things, we just take screenshots. There’s a heavy dependence on visual evidence, most of which ends up clogging up our phones. Our memory is changing because now we have this technological extension of it.

Yes, now it’s so much easier to do—you don’t have to take the film, loaded in and out of your camera, have it processed. It’s like a composite of all the sensory information you have been processing. It’s just piling up in your phone’s hard drive. But what does it all mean?

Right, what does it all mean? Data collection is not thinking, processing, making meaning. Your series wasn’t just about remembering–you were trying to make meaning of it. And it’s only through meaning that there’s any kind of catharsis.

Yeah, there it is.

And, we are not talking about moving on, which is such a strange statement.

Oh yeah, my mother would say, you just have to deal with it and move on.

The instinct of a lot of people is to say you need to move on, but most of us learn to live with trauma.

That’s sort of what made me go out and photograph. There wasn’t a point of me escaping this stuff. It was my life. The criminal justice part felt like I had no control over my life during that time. I couldn’t make any future plans. I just had to be in this, and I decided to turn and face it. The best way to deal with trauma is to try to process it. There is a sense of exposure to it in a safe way. In a therapeutic situation, they ask people to go through this again in their heads where you are actually going to be hurt, but you have to understand this will always be a part of your life. I don’t think society is very good about helping people process trauma.

There is no coping mechanism—we don’t know how to cope in difficult situations, when things are not going great, or when there is trauma.

And the tendency to make other people responsible for it. It’s a television and internet culture where things become black and white, oversimplified, and they’ve got to fit into this format, like a 30-minute television show that’s supposed to have a beginning, middle, and end. Stories are very simple, extremely linear.

I was also uncomfortable in newspaper journalism because of the format, self-editing, and the sense that if you pissed these advertisers off, they are not going to give us the money that we need to keep doing this other work that’s important.

It’s too complicated to go into the history of this neighborhood why people are angry at each other. If you really wanted to delve into the injustice of building this freeway infrastructure right through the middle of this neighborhood and the way it completely disrupted and traumatized all the lives of these people. No, it was actually just a shooting, and the cops showed up, and you have to talk about that in 10-12 paragraphs, then there is no context.

It’s so hard to live with the things that unfold right in front of your face on the subway or if you are somewhere else in America on the freeway, and you don’t understand the context of a person’s life that’s cut you off or yelled at you. And it’s really impossible to have all that context. The best we can do is to understand that it exists—it’s not a black and white world. There is so much context with everything, and if we can just start there and know that that’s a part of having empathy, for one, as a society and as individuals.

I felt the need for people to understand what had happened to me. And I needed to understand and bring awareness to all these other people who were dealing with brain injuries that had totally altered their lives. This project not only describes that experience of having a brain injury, it maybe helps us reflect on our human experience in general and how memory serves that, how context serves that, and how memory serves context.

In some of the photos, the subject is central, grouped close, and harshly illuminated against a near-black background. There is nothing strange happening per se, but you get the sense of what you describe as an “altered life experience.” What was your intention?

I became interested in using flash and was using it pretty regularly up until then, but I had not quite done it in this way before. There is this sense that the flash changes the way something that’s right in front of you looks. You can’t even see it in the camera when you are doing it. It’s so instantaneous, like a 1/60 of a second or less that makes an impression on your brain, that’s how much you see. Nonetheless, the people are existing in that space that you are photographing exactly where they’re existing; it’s just that you are looking at it this way that you don’t normally look at it, and I think that there is something revelatory about it.

What you are aspiring to when you make art is to ask questions. Just that notion that you are looking at these people in a way that you don’t normally see them and just doing that is enough to make you start asking questions about your own perceptions. That’s something we should be doing. We should always ask ourselves how we are looking at something and what is it that we are actually perceiving.

When you returned to Sierra Gates, you weren’t an outsider looking in, seeking out a story. Would you say your job as a photojournalist is to remain outside or objective in relation to your subject?

That was my training, theoretically, to maintain some objectivity. Still, the thing that I learned from this one guy at the University of Missouri is there’s no such thing as objectivity. He was sort of going rogue. He pointed out the window. He said, you see that intersection there, I could put one of you on all four corners, and you can stand there long enough and eventually there is going to be a car crash, and you are all going to have a different story about how that happened because of your perspective. We are all coming at the world from the perspective that we have and our own experience. The notion is that you should be open to context, but you are also who you are with your experience and your perspective, and you need to understand you are bringing all of this. You are going to understand what I am saying in the context of your own experience. We need that sort of acknowledgment all the time.

I’ve come close to making a book about this—there is a little bit more I have to photograph. I know that to make a really meaningful book that I have to address why I haven’t made a book of it already. That’s again, the burden of memory and having to revisit it. It’s a little traumatic to me the idea of having to go back to this so deeply to do this book. I am a little afraid of the trauma that it might dig up. At what point is it healthy to do that.

It’s what you were saying earlier, there is no black and white here, no beginning, middle, and end. You are still living with this, and perhaps by putting it in a book, closing the cover would mean that it’s over.

Yeah, like how do I summarize it?

Can a book encompass everything—all of it?

I have to make peace with the idea that that’s not really going to be possible.

John Trotter, 59, a native of Missouri, began his career as a newspaper photojournalist, working mostly in California. His greatest achievement has been to survive a work-related attack and traumatic brain injury in 1997 and to eventually learn to be a photographer again, resulting in a body of work, The Burden of Memory, about the violence itself and the brain injury rehabilitation residence where he lived for over two months. Since 2001, he has been working on another personal project, No Agua, No Vida, about the human alteration of the Colorado River. He is a founding member of MAPS photo agency.