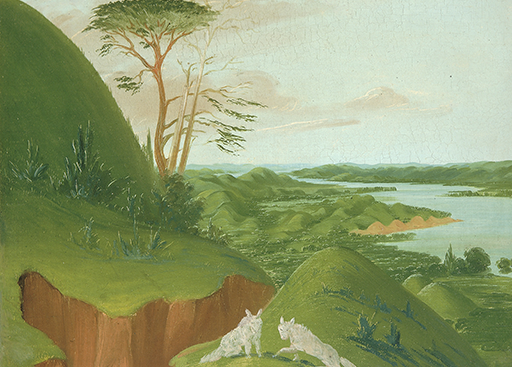

Catlin, George. River Bluffs with White Wolves in the Foreground, Upper Missouri. 1832, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Coda

by Marion Lougheed

Taha jumped when he noticed the man on the stool, half-hidden in the shadows of the leafy trees. How long had the man been there, tucked away with his canvas and his paints, silent as the white-tailed deer Taha had glimpsed with his grandmother last summer?

The man peered at his canvas through glasses that caught the sun, threw its sharp edges back towards the lake. His beard was a cloudy red. Taha stared until the man looked up. Neither of them spoke. The man raised a hand, then put a finger to his lips to indicate silence, or maybe that Taha shouldn’t tell anyone he was there, then he went back to his work and Taha went back to skipping stones.

Taha didn’t like being watched by a stranger. He was only nine and his teacher said strangers were dangerous. He didn’t like hanging out in the woods all alone either, which was why he’d come to the lakeshore in the first place. He tossed another stone, but his aim was off. It plunked into the water.

Last summer, Taha’s grandmother sat up front in the car beside his mom, with Taha and his dad in the back for the long drive to their campsite, just like they’d done the summer before and the summer before that. Construction on the highway slowed them down, big men and a few women with orange and yellow clothes and white hardhats like protective shells, matching cones funneling the traffic down a single narrow lane. On the second day of camping, while Taha’s mother meditated cross-legged on the picnic blanket and his father wove art out of sticks and flowers, his grandmother took Taha for a walk. She sat him down on a log in the shadow of the maple trees, holding his hand in hers, both reddened from scrubbing dishes in cold water. “There are wolves out here,” she whispered.

Taha could no longer bear the painter’s silence. “Are you camping too?” he asked. For his parents, it wasn’t so much a camping trip as a silent retreat, which meant that he could talk to them, but they wouldn’t answer out loud. They might gesture or nod or even occasionally write something down, but he always saw that quirk in his mom’s forehead, the droop in his dad’s smile, like Taha had interrupted their progress and now they’d have to start all over again. The painter was someone to talk to, at least for a little while. Taha would run at the first sign of weirdness, or if the man offered him candy or food, or a ride in his car, or showed him a leash with no dog attached.

“I’m staying in a yurt,” the man said, his voice rich and brittle like crème brûlée. A breeze rippled the lake, mussing the sky’s reflection, the line where the sun glimmered, and the few splotches of pale green, the mirrored clouds, smudged like someone had stepped on them before they dried.

Taha didn’t know what a yurt was, but he guessed it meant the man was camping in the park.

“I don’t mean to be rude.” The painter swivelled on his stool, looking Taha square in the face for the first time. Taha stepped back into the water, even though he was several meters away from the man. He tensed, ready to run. The deeper water wrapped warm around his bare ankles and calves, wrinkles spreading outward from his legs.

“I don’t mind you hanging around.” The man waved his hand vaguely. “But I really need to finish this painting.”

“Why?” Taha didn’t want to be rude either, but it was refreshing to hear another human voice after four days of nothing except the distant chatter and laughter of the other campsites when he went exploring. Taha’s parents always camped at the most remote campsite, in the quiet area, where you weren’t allowed to have pets or radios. The long, high whistles and grating caws of early-morning birds woke them all with the sun, when the blanket of mist had yet to uncloak the lake, and sometimes he could hear the haunting, hypnotic call of a loon.

The man set his paintbrush on his tray, stamped his worn but polished workboots like he was trying to bring circulation back to his feet. He smiled, but in a way that made Taha feel sad. The wind ruffled the lake and the leaves.

“Why do you need to finish the painting?” Taha repeated.

“It just needs to be done, that’s all. Or I won’t finish it.”

The man’s vagueness was starting to irritate Taha. He picked up a stone, flat on one side with tumorous bulges on the other, concentrated to throw it straight across the surface of the water, practicing the angle a few times, one eye closed and then the other, before letting it fly. With so much weight on top, it flopped into the stream without skipping even once. Taha frowned. He waded even further into the water, wetting his shorts along the hems where they dipped in, but the summer sun sucked the moisture out of them within seconds. He slipped on something slimy, almost lost his footing, but then mud sucked in his feet and glued him to the bottom.

He considered heading back to the campsite. He was getting bored of skipping stones, and the painter obviously found him annoying. But his parents would probably want him to lie down on their big cloth with the sandal and holy basil woven into it, so they could set a piece of amber on his bellybutton, lemon quartz on his solar plexus, rose quartz on his heart, and all the rest. Then he’d have to lie there unmoving while his legs itched and ants, real or imaginary, crawled up his scalp. Once his chakras were aligned and unblocked, his parents would make him take a nap, since lack of sleep could re-block his chakras. Taha didn’t want to take a nap. He wanted the painter to talk to him.

But mostly he wanted to wander with his grandmother. He wanted to see a wolf.

On last year’s excursions away from the campsite, Taha and his grandmother had seen beavers and moose, gray jays and loons, even a couple of black bears, shy as they were. But no wolves.

“I promise you they’re out there,” his grandmother assured him from the front passenger seat as they drove home after the family’s week of camping. The road was clear of construction today, because it was a Sunday. The cones and barriers were still there, but pushed off to the sides. “We’ll see them next year,” she had promised, and he’d believed her.

The painter rolled his brush in his paint, dabbed the canvas. Bored and a little irked by the man’s lack of responsiveness, Taha started away from the lake, aiming to head into the forest where he could watch for wolves, even if he had to sit silently all alone.

“It’s just that soon I won’t be able to paint anymore.” The painter’s voice sounded thicker, heavier, taut, like a slingshot pulled back but not released.

Taha stopped, surprised. “Why not?”

The man didn’t reply. His attention stayed on his work, one hand poking the canvas with a smaller brush. His glasses glinted in the light, but Taha could see the grim press of his mouth. Intrigued now, and wondering if maybe the painter did want to talk after all, Taha went back to tossing stones into the water, not bothering to search for flat ones or trying to make them skip. His supply of suitable rocks was running low anyway. He threw them overhand, then sideways like a baseball pitcher. Even after a summer of practicing in the park near their house in the city, he couldn’t master the wrist flick of a cutter pitch, the kind that curved away from the batter at the last minute. Of course, the stones weren’t round or the right size, but it was a change of pace from skipping them. A far-off canoe blotted the lake, a dark spot against the sun descending towards the horizon. Sparkles on the lake burst like electricity.

A few days before Taha’s family left for their annual retreat, his grandmother fumbled with the buttons on her pale blue shirt, the one with the ruffles down the chest. Her nimble hands had forgotten the motion and she laughed, but Taha saw the lines of fear around her mouth. Taha had to do them for her, awkwardly keeping his eyes averted from her chest but then having to look at what his fingers were doing so that he could fit the buttons through the holes. In the last few months, she sometimes called Taha by his father’s name, or his uncle’s, and one time in December she’d shown up at their door in nothing but her bed socks, nightgown, and curlers, shaking with cold, her face slack. As much as she’d insisted in the spring that she was fine, Taha’s dad refused to let her come camping with them this year. “What if you get lost with Taha?” he’d said. She opened her mouth but snapped it shut without a word. And that was that.

Taha thought he might just as likely get lost on his own, but nobody asked him.

Taha waded out of the water and sat down on the grassy bank, littered with twigs and dried leaves. The twigs stabbed into his legs and butt, so he shifted until he found a comfortable spot. A gray jay clicked and chirped in a tree nearby. Gray jays were the cutest bird, he thought. He picked at the papery layers of a pinecone.

“Do you paint a lot?” Taha asked the man now.

The painter smiled his sad smile again. “I used to. Had a few pieces in shows, but never my own exhibit or anything like that. One of my works is on the wall in a restaurant near here. Maybe you’ve been.” He gazed through his thick glasses, off into space, and Taha tried to follow where he was looking, but all he could see was a clearing in the trees.

With some disappointment, he noticed the slanted shadows. “I have to go for supper,” he told the man, who appeared to have detached from the conversation again. Maybe there was something wrong with his mind, like Taha’s grandmother. “I’ll be back tomorrow though.” It was a question and the man nodded. “I’m Taha, by the way.” He walked right up to the painter, stuck out his hand boldly and the man took it in a solid grip that didn’t crush him the way some adults did.

When Taha got to the lakeshore the next morning, the man was already at work, his face close to the canvas as if he were inhaling its scent.

“Hi,” Taha said when he caught his breath. He’d run from the campsite as soon as he’d finished the morning yoga routine with his parents. Today they focused on energy, so they spent time on low cobra, locust pose, and upward salute. But then they always did upward salute in the mornings. Sometimes in the evenings too.

The painter raised his right arm in a gesture that could have been a greeting or a request for silence. Taha frowned and started collecting pinecones.

A while later, the man put down his paintbrush. “I’m done.” He closed his eyes and sighed. His smile looked content today, not the sad look from yesterday. Taha wasn’t sure if he should interrupt while the man sat for a minute. He looked like he might be doing a breath meditation, eyes closed, chest moving slowly up and down. Finally, he turned to Taha. “Want to see?”

He nodded eagerly and the man beckoned him around to the front of his easel. The canvas showed the lake, reflected sunlight glittering, a canoe in the distance – and Taha tossing a stone, hand outstretched but empty. The painting had caught the stone in midair, above the rippled circle where it had skipped once already. The trees broke the light into fuzzy streaks. Taha noticed that the whole picture was fuzzy and squiggly, just like the gray one with boats and water and an orange circle for the sun that his dad had brought home from the flea market one day last fall.

“Why is it so blurry?” he asked.

The man gave it a quick glance. “Is it? I guess some people would say it’s impressionistic.” He laughed, but his Adam’s apple bobbed with difficulty. “Did you know that most of the impressionists had bad eyesight? So I guess there’s a gift even in going blind.

“Here,” he said. He held out the painting to Taha. “It’s for you.”

Taha moved close enough to take it with both hands. It was lighter than he expected, like a kite just starting to tug in a breeze.

Marion Lougheed is a PhD candidate in social anthropology at York University in Toronto. Her short stories have appeared in Paragon, Landwash, and The Basil O’Flaherty. She has driven across Canada, from Vancouver to Charlottetown, and once lived on a 27-foot sailboat with her partner Jason.