The Belt

by Rob McClure Smith

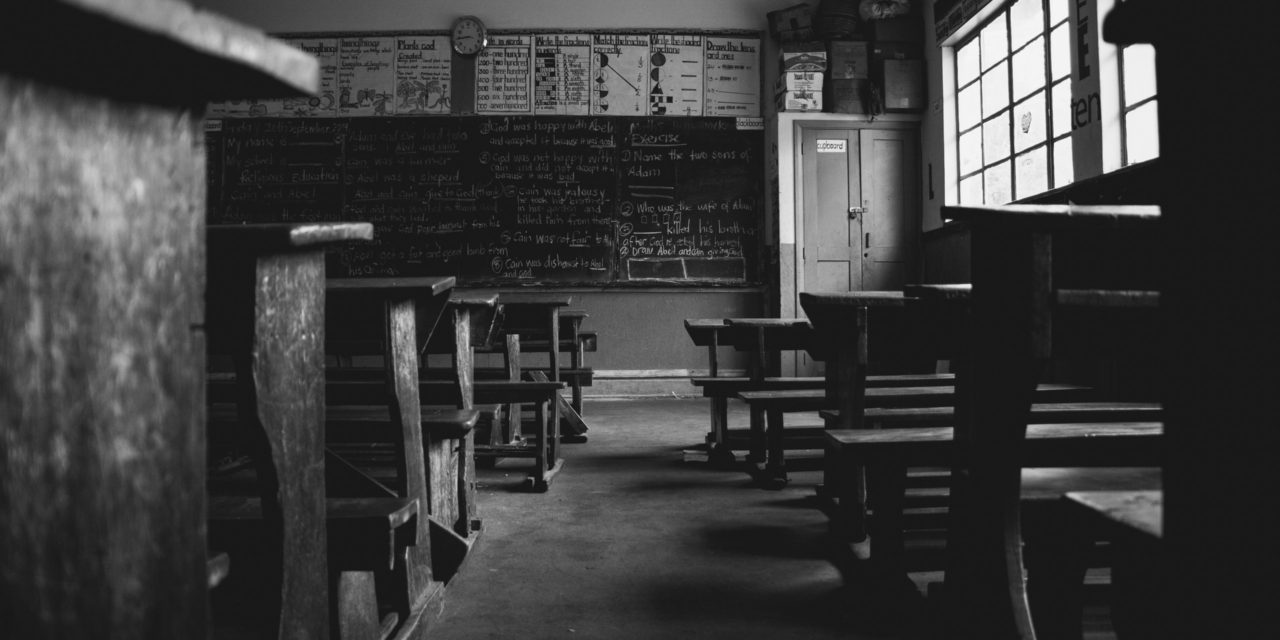

I remember the first time I was whipped by a leather belt. I don’t recall much about the pain, except that it definitely stung. The humiliation is what I remember most. It is humiliating to be struck by a leather belt before an observing coterie of your peers. You can show no emotion during the ritual obviously, no semblance of fear or tear. So I stretched out my arms so they met in front of me, one hand supporting the other, and I closed my eyes and the belt was raised and brought down hard along my hand, from fingertips to wrist, three times. My offence was the throwing of a snowball. The belter was my teacher. I was eight years old. In retrospect, I think it is somewhat remarkable that a teacher was licensed to hit children with a blunt instrument, even if for their own benefit. Then again, in retrospect, I don’t know what to think about any of it.

The English began to limit the use of the cane in their schools in the 1960s. But the tawse remained popular in Scotland among parents and teachers. The available historical data is scant. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, 84% of boys and 57% of girls in comprehensive secondary schools claimed to have been belted, over a third of the boys saying it happened regularly. In 1972, according to teacher logs for that year, the belt was deployed 30,000 times on an Edinburgh school population of 80,000. Five hundred girls between the ages of five and eleven were among the 4,000 children belted in the spring of 1973 alone. That year the local education committee in Edinburgh voted to phase out corporal punishment, a decision abandoned after strong opposition from teachers and parents. According to a 1980 survey, only one in twenty Scottish boys escaped being belted during their entire school career.

The word ‘tawse’ is derived from the method used to cure the animal hide known as ‘tawing.’ The tawse was also referred to (by those on its receiving end) as the Toosh, the tag, the tash, the scudge, the scud, the leather, the belt, the strap and The Lochgelly.

I was belted frequently during my schooldays. My favorite English teacher belted me once for forgetting a book. I later found the book (The Mayor of Casterbridgeit was I recall) in another pocket of my satchel, and he laughed when I told him I’d actually had it with me all along. I was belted for laughing at another kid’s assertion in Latin class that Nero shot his mother. I was belted for being a wee smart-arse (with a proclivity for bad puns) in general. Strangely though, what I recall most vividly is seeing others being belted in front of the class or in the corridors outside. Is this repression on my part? Did such observation do lasting psychological damage to me? I can’t begin to fathom that, am tempted only to smirk and say I didn’t give a tawse.

The tawse, sometimes spelled taws (the plural of old Scots taw, thong of a whip), was the primary implement of educational corporal punishment. In Scotland, the tawse rigorously enforced and maintained classroom discipline. A tawse is a strip of leather, one end split into tails. The leather thickness is variable. Typically, pupils were instructed to hold out one hand, palm uppermost, supported by the other hand below. This arrangement made it difficult to move the hand away during the downstroke and ensured the full force was taken by the hand strapped. The punishment usually took place in front of the entire class, to act as a deterrent. A tawse-swasher was, therefore, one who wielded a tawse adroitly. There were many talented tawse-swashers.

John J. Dick Leather Goods was the manufacturer in the Fife town of Lochgelly who made 70% of tawses (or Lochgelly specials) used in schools. The trade was supplemented by exports to Scottish parts of the old empire like Malawi and New Zealand. The tawse was made by hand. Two feet long strips of leather cut from pre-tanned and pre-curried hides then dressed with the tongues cut halfway up the middle. (The leather was also rumored to be dipped in whisky to provide that extra nip). This specific tail design provided the satisfying snap when it struck the child’s hand. At the same time, the tails were also carefully ‘edged’ to prevent the actual drawing of blood, which would be unseemly.

There was this music teacher called Stallard who taught in a two-classroom temporary mobile building on the periphery of the high school campus. Everything that happened in his classroom was audible during our history period next door, echoing resonantly through the plywood. On occasion, there was an uncanny symmetry to the diverse subject matters. The bones of Saint Saens’ skeletons rattled away during a ‘Great Battles of the Great War’ study period. But more usually, it was a dissonance, the Queen of the Night popping a vein during an explanation of the Corn Laws or Holst’s Mars erupting into the subtleties of Bismarck’s foreign policy.

This Friday afternoon, a time when kids were restless and edgy anyway with weekend yearning, there was a commotion in the alcove outside the classrooms, a shouted command, and the subsequent thwack of leather on skin. We all leapt to attention, an electric charge running through the room, the scent of fear burning the air sultry. Stallard was a belter with an explosive temper and a reputation as someone who could really ‘draw’ the tawse. Usually, you heard two crisp cracks, the shuffling of footsteps and the closing of a door. Sometimes, if it was a girl, sniffles for a time. Mild sniffling was acceptable in a girl. On this occasion, though, there were six dull smacks. We stirred uneasily in sympathy. Dull meant hard. Each smack was followed by a muffled conversation and what sounded like shallow intakes of breath. Then, abruptly, the door flew open, startling our teacher as much as anyone, and Stallard stood there in the frame, red-faced and furious, fingers clenched pale around the collar of a little boy’s blue blazer. The boy sputtered tears, his face was streaked every which way, his little tie damp and askew.

“Have a gander at this, will you?”

“Sir. . . ” The boy looked all around the classroom wildly, in utter mortification.

“Have a good look at this. Here’s your hard man.” Stallard shook the boy like a dishrag. “You’re a real hard man, aren’t you? Glasgow hard man? See the wee Glasgow hard man? See him? Blubbering like a wean.”

The boy winced in horror, his world in pieces. “Sir. . . Please. . .”

“Big wee hard man, huh? I am so scared,” Stallard sneered. “Get the hell out.”

He tossed the kid back through the door and slammed it behind him. Our teacher tried to get the class back. “Open your books at…”

Outside, a roar: “GET THEM UP. CROSSED OVER. TWELVE O’ CLOCK.”

The thrashing went on and on keeping metronome time to the sobbing. Stallard, the musician, had quite a talent for rhythm. This wasn’t six of the best, more like twelve of the worst. I understand it now though. Stallard studied music at Glasgow University. He was an enthusiast with dreams of being a Celtic Sibelius. Instead, he woke up one day and found himself teaching the music he loved to unappreciative teenagers in a decaying working-class town, kids who listened to The Clash and The Undertones on Radio Clyde. The years must have stretched out before Stallard like an abyss, his world in pieces. But I should mention this also: That afternoon, the history lesson went swimmingly, one of the best our teacher ever had. It was a unit about the Peterloo massacre and its consequences and I have never forgotten it.

Teachers typically kept their belts in their desk drawers, although some looped them over their shoulders or kept them in holsters gunslinger style. They were encouraged to belt pupils in front of the class because the system of corporal punishment was designed primarily to instill fear. The belt was used widely in primary (ages 5-11) and secondary (12-18) schools. Girls and boys were belted alike. Age and gender were irrelevant to the principle of discipline.

The ideal tawse was fast to manufacture, easy to use, yet firm when applied diligently. In the early 1970s, demand for the tawse was so strong a modern manufacturing method was required to keep up with the backlog of orders from teachers. This led to Dick Leather Goods having to create a state-of-the-art three-phase cutting press, allowing mass production on a factory scale.

During my own teacher training practicum in the south side of Glasgow, the History Principal drew a belt out of his briefcase and handed it to me. It was long and thin, an expensive brown leather woven at the edges with intricately patterned red thread. The belt was smooth to the touch and smelt new, leathery fresh. It was a quite lovely thing.

“Ideally, you would never have to use it,” he told me. “The threat would be sufficient in itself to keep the wee bastards in line. Deterrence. Like the nuclear missiles on the American submarines over in the Holy Loch, right? Have a demonstration on the first day though. Set the tone for the year. Get the word out on the jungle telegraph that you’re no pushover. This game is all about reputation. Establish Mutually Assured Destruction, if you will.”

I handed the belt back to the Principal and he took a piece of chalk and positioned it on the desk in front of him. He whipped the belt up high over his shoulder and down again in one fluid motion, its arc a blur, the aftermath just a thin trace of white dust on the desktop.

“See? Get it right on the first day, no problem. Don’t fuck up your demo though. The wee cunts will laugh at you. Practice till you can do it in your sleep. I use it, on average, about ten times a year after the initial exhibition, and only on your real mental cases. I’d never use it on an older lassie because that’s a bit too kinky for me, downright uncomfortable. I mean, what if you went and got an accidental hard on? And never ever when you’re angry, always important to keep the head in a crisis.” The Principal draped his arm around my shoulders, gave me a reassuring clamp. “If you get the reputation as the one doesn’t belt, in a place where everybody else does it to beat the band, you are well and truly fucked. They will eat you alive, son.”

In 1976 Grace Campbell, whose son, age 6, attended St. Matthew’s Primary School in Bishopbriggs and Jane Cosans, whose son attended Beath High School in Cowdenbeath, raised an action in the European Court of Human Rights objecting to corporal punishment in Scottish schools without parental consent. In 1982 they won their case and local authorities, suddenly overwhelmed by the bureaucratic turmoil of acquiring parental permissions, began phasing out the belt. However, private schools continued the practice till 2000.

By the end of the 1970s, it was difficult to source leather thick enough to manufacture the heavier versions of the tawse. The increasing preference for leaner meat meant that cattle were being slaughtered younger leaving fewer bulls available to provide a supply of thick leather. For a while, buffalo necks furnished a substitute but were more aesthetically displeasing with a rougher texture and darker hue.

The headmaster of the Academy sat puffed and bloated as a bullfrog in the dark of his office. His voice was a lilting County Kerry brogue, the most vicious of accusations muffled in syrupy sweetness, as now, for instance. “Would you be calling yourself an arrogant person?”

“No, I wouldn’t.”

“What would you be calling yourself then?”

“I’d say I was. . . strong-minded. Something like that maybe.”

Fagan extracted a sheaf of files from a metal cabinet, selected one and sniffed. “You had this very impressive record as a student-teacher when you were at Jordanhill.” I smiled, felt his fish-pale eyes drowse over me, and realized at once my mistake. “But this wouldn’t be the student teaching. This would be the real deal.”

“Well, I can’t do it.”

“Well, it’s important for you to realize you’re not the first one’s said that. I want you to know that. It’s important for you to realize that I’ve had others sitting right where you’re sitting. Many’s the one. Sitting right there. In that there selfsame seat.”

“I just can’t do it. It doesn’t feel right.”

“We are catering to a different clientele here. You can’t be the one who doesn’t use it. That’s the crux of the matter. They take advantage. They are savages, regretfully.”

Fagan suddenly pulled one out of the top drawer and laid it on the table in front of me, smoothing it out. He was the kind of person who would keep a pet snake. “There. Take it. Then when you need it, you’ll have it at hand. No pun intended. It’s one of me spares.”

I wasn’t sure if the expression on my face made any sense, but couldn’t figure how to change it without hurting myself.

“Oh for the love of Christ, just take it, man. Taking it shouldn’t mean you’ll use it, right? Think of it as a challenge to your integrity and self-righteousness.”

I took my self-righteous integrity out for a walk to my girlfriend’s house that evening. “Were you ever belted at school?” I asked her.

“Aye, a bunch of times. It stung like crazy. The teachers never really drew it hard with the girls though. They went easier on us. It’s kind of sexist when you think about it.” She glanced at me mischievously. “Woman’s liberation will entail girls getting as good a hiding with the belt as boys. We should start a campaign for it.” She laughed bitterly. “But it is quite the tradition. Boys I knew used to rank the teachers on how good they drew the strap. Honest to God, I think there was a definite correlation between success in the classroom and sadism.”

“I’ve come to hate it,” I told her.

“Don’t use it then.” She sighed, bored by the conversation now. “Be a milquetoast then. I remember back in the day Mrs. McIntosh didn’t use it on us. This was in primary school. She used to cuff us around the ear with the wooden end of the board scrubber or she’d sometimes pick us up by the hair and swing us around the classroom when she totally lost the rag.”

“My god,” I said.

“Well, six-year-olds can be a right handful in class, you know?”

The display of seven tawse in the collection of the Museum of Childhood in Edinburgh is among the most popular of its attractions.

Classic leather tawse are today pored over like works of art, with collectors willing to spend hundreds of pounds for a mint condition four-finger ‘Huntly’ or a heavyweight three-finger ‘Lochgelly.’ Retired schoolteachers are much sought after in the collector’s market for tawse they may still have. Of course, retired teachers often want to keep and display them on their own walls, making the memories palpable, and it is rumored that in these more enlightened and exploratory times the classic Lochgelly has a new clientele of S&M devotees who claim the specific tingling aftermath of the tawse strike provides its own unique frisson.

It is difficult to apply the morality of one generation to a previous one, although these days we often do in a fog of self-righteous integrity, altogether woke and enlightened. In the 1970s the formal abuse of children in Scottish schools was normalized and unquestioned. It was the very air we breathed. I was very afraid of violence in the classroom, but I was more afraid of the violence outside it, in the playground, in the streets, and in my own home. There were very many adverse experiences available to a young person in the West of Scotland in those days. There still are. Growing up in a council-housing scheme, a desert with windows as the joke went, surrounded every day by economic deprivation and urban decay, religious sectarianism, drug abuse, and rampant alcoholism, getting leathered by a teacher occasionally was the least of my worries. The belted earned the respect of their peers; unflinching, we walked a little taller for a day. Who knows, perhaps a culture of violence is necessary to instill some semblance of ethics in a violent culture. This I assert with trepidation and regret and embarrassment for I still don’t know what to think about the tawse now, even with this much historical and geographical distance from those days, and that locale. To essay is to try. But I can’t begin to try in this essay to process the lasting damage to a person, to a system, to a culture. Maybe the reason for that is the question I have left so carefully unanswered here. It is this one: ‘Before leaving Scotland and school-teaching forever, before putting an ocean between you and the person you were, did you ever break down and use the tawse yourself?’

Rob McClure Smith‘s work has appeared in literary magazines in the United States, including Chicago Quarterly Review, Gettysburg Review, New Ohio Review, and Confrontation. He has also published in European magazines like Barcelona Review, Warwick Review, and Manchester Review. He has had work special mentioned in the Pushcart and Best American Series.