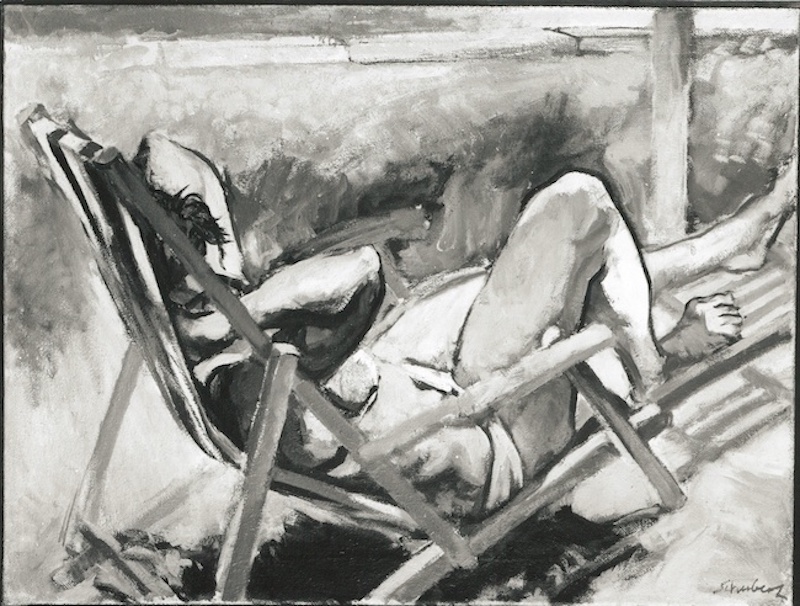

Schubert, Manfred. Im Liegestuhl. Deutsche Fotothek

Those Were the Days, My Friend

by

Beth Escott Newcomer

On those summer camping trips to Wisconsin, I was glad to forgo air-conditioned Holiday Inns. I rallied around the campfire, toasting my marshmallow by gleefully setting it on fire, taking my turn at Charades, and later, after you kids went to bed, chortling over the dirty stories your father and Scott—a pair of preachers’ sons—told.

It was worth it, in those days, because Joan and Scott Sebastian were our best friends; I loved them like the siblings I never had. Being with them and their kids took the pressure off your father and me, somehow made us seem easygoing, more like a postcard family than how we really were.

You must’ve sensed the friendly competition between Mrs. Sebastian and me. When it was her turn to make breakfast for all eight of us, she would fix bacon and pancakes and scrambled eggs and would serve it up on tin camping plates—using nothing more than that little one-burner camp stove and the open fire. But instead of matching efforts with her in these rustic culinary pursuits—and believe me, I could have figured it out if I’d wanted to—I went the other way. When it was my turn to make the breakfast, I’d stand in the trailer doorway in my nightgown and toss out boxes of Snack Pack cereal to you kids, saying, “Catch!” and “The milk and juice is in the cooler,” then crawl back into my sleeping bag with Joseph Heller or John Fowles.

Mrs. Sebastian, Joan, was always cooperative and going along with everything, seeing everyone else’s side of things. I guess that’s why I liked her—an “opposite of me” personality. She was a good listener, and I, as always, was a good talker. But being around her seemed to make me want to swim upstream, to pronounce my opinions even more loudly, to roundly insist that the rest of them could not possibly understand whatever obscure point I was making. If she was going to be the sweet one, I needed to be the smart one.

She was cute and perky, watched what she ate, looked great in her two-piece bathing suit. Maybe I was rapidly losing my girlish figure and did not care to expose that fact in public, or maybe vanity was not my biggest priority. Her language was always careful and safe, like her cooking. I sharpened my words on a whetstone.

Of course, none of this helped things with your father.

It is dangerous, even now, to tell you that I had my suspicions about your father and Joan, especially on those Sunday afternoons back home when the two of them would take you four kids bowling, or ice skating, or to run the dogs out at the lake, and I would be alone in the house. If I told you that it all began like a subtle, rotten smell, why, you might ask, didn’t I track down the source of that smell? Why, if I thought your father was unfaithful, did I do nothing about it?

I would have told you at the time, when you were thirteen, it was nothing, meaningless. And even if it wasn’t—even if they were quickly burning the love letters they wrote to one another, even if they were setting up rendezvous at the Ramada Inn, even if they already had pet names for each other—your father’s love for you and your brother was big enough to endure our crumbling marriage. Even after he stopped loving me, I believed he would never leave you.

You think I drove him into her arms, and maybe I can’t change your mind about that. All that arguing. Your father and I had cut our teeth on topics like money and the proper discipline for you kids and who was responsible for what around the house, but as we learned more about who we were and what we wanted, we pinned targets on each other’s soft underbelly. Eventually we no longer required a subject at all—the tone of his voice or the look in my eye became a well-worn shortcut to the battlefield. I added insults to my petty parries. He sprayed the driveway gravel all over the lawn when he peeled out in that damned Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme.

Could you understand that whenever your father left the house, it was pure heaven for me? If I told you I was happy to be free those Sundays, free from his false morality, free from the labyrinth of rules that must be obeyed and obligations that must be met? Can you see how delicious it was for me to have the whole house to myself all Sunday long? To be able to wander its rooms, to smell your pillow and peek at your diary pages? To smile instead of scowl at the way your brother shoved everything under his bed and pronounced his room clean? To not have to do or be anything for anyone else for an entire afternoon?

Could you forgive me if I told you that, by the end, I suspected the worst, and though I could see its contours under the skin of each day, the affair was a kind of relief to me? Rest assured if they decided to come clean, to make it all real, well then, they would be the sinners, not me. He would be the guilty one, and in this way, I would win.

Maybe I had not formed these thoughts quite so clearly on the day your father informed me that it would be best for everyone if we separated for a while. A person can never be fully prepared for that black and bright moment of recognition when what was merely suspected turns concrete and walls you in alone with the truth. Up to that moment I did not believe he would leave us. I felt obliterated, dismissed, dissolved. But I did not show him my feelings. Instead, I stood up straight and said, “Yes, Sam, I guess that’s best…for everyone.” After he left I watched the bathroom floor as it came up to greet me in slow motion. When I came to, I picked myself up, washed my face with cold water, and said to my reflection, “Yes, I guess that would be best.”

I drove to Miller Park with a loaf of day-old bread, sat on the bench by the lake, and fed the ducks. They told me Sam and Joan would never find true happiness because I would still exist in the world, bearing witness to their sin. Standing martyred on the sidelines, I would not die, but I would not live either. This would be their punishment.

Later, when you went with them on all those road trips to Colorado and Florida and God knows where else, playacting a happy family, did you stand with me? Did you stare them down even as you stared out the back-seat window of that hideous brown station wagon as it rolled down the interstate, Sam in the driver’s seat, Joan in the mommy seat?

I know you did, honey. We stared them down together, didn’t we?

Beth Escott Newcomer’s stories have appeared in many literary journals, and have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and for Best of the Net. She was named an Emerging Voice as part of the Los Angeles New Short Fiction series in 2015, and in 2016, her story “Survival Skills” was featured in the Los Angeles Lit Crawl. She co-founded Chicago’s Clybourn Salon performance venue in the 80s, and was a member of the Amok Press collective in Los Angeles in the 90s. She lives in the high desert near Joshua Tree National Park with her husband and a pack of dogs. Learn more at bethescottnewcomer.com