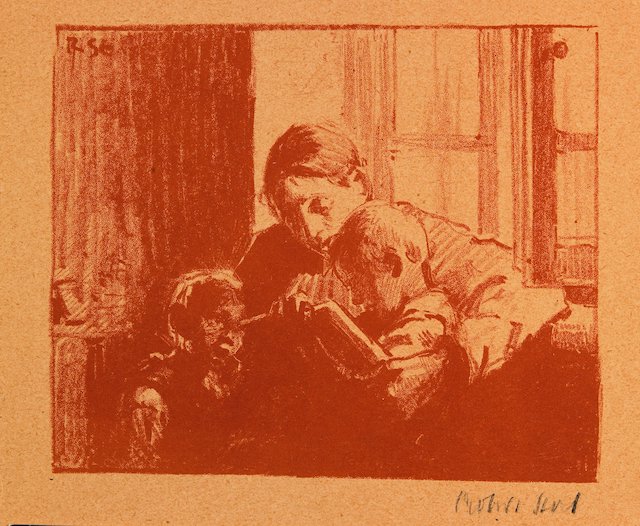

Sterl, Robert. Mother and Children. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

In Three Days, Beatrice Dies

by Thea Swanson

decision

It is time for Beatrice to die. This, she knows. But first, she must drench her children in love. It is clear that everything is falling apart, so she must go. Before she goes, she will give each of her three children one perfect day.

waking calliope

Oh, first-born child! Oh, daughter of Zeus! Bea named you rightly. Sixteen and glorious and headstrong. So often you have butted heads with your mother.

“Morning, Sleepyhead. Can you be ready in an hour?”

“God, Mom. Let me wake up. Jesus.”

Bea’s resolve begins to crumble, as it always does, but she reminds herself that this is their last day together.

“Okay, Sweetie. Whenever you’re ready.” Bea walks back to her bedroom. Last week, she would have locked the door and smoked near her window. A relatively new habit, only a year old. But today she doesn’t need to ease the pain. The pain will be gone soon enough. There are more important things to tend to.

Bea sits by her window. Outside, the sun shines on this summer day. Bea waits by the window for hours and does not move. It is Calliope’s day.

the mall

Again, Bea sits and waits—this time, outside the changing room. In Bea’s hands are three miniskirts and six camisoles. It has been a year since she resigned herself to her daughter’s taste in attire. It has been a year since Bea changed her own attire. Before, Calliope would ask her why she dressed like a nun. But Todd’s fling made Bea look at herself, at her tied-back hair, at her unpainted nails. At the first sign that something was awry, Bea let her hair down, bought sex toys, opened her eyes to the broader female population and decided to join it. She painted her short nails that had stopped growing because of lies, because of dinner receipts found in her husband’s day-planner, because she was losing her mind.

“What d’ya think?” Calliope’s butt cheeks poke out.

“Umm, a bit short? Look in the mirror,” Bea says.

Calliope turns towards her reflection. “I like it.”

Bea nods her standards away. They matter none. Nothing Bea does or thinks, or ever did or thought, matters. Of this, she is clear.

“Calliope.”

Calliope halts before entering the changing room, holds the curtain.

“You look beautiful.”

Calliope lights up, a smile that takes Bea aback, burns her heart. It is a smile from yesteryear, from a long braid and glasses.

Bea and Calliope head into another store on a search for brassieres. Calliope fingers the lace on some, scowls at the preponderance of padding on most. Calliope knows that much padding won’t feel real to her boyfriend, that all the girls will be able to tell.

“They didn’t have all this when I was young,” Bea states. “If you wanted to look bigger, you stuffed your bra with tissue. Now, girls feel like they’re too small no matter how big they are.”

“How would you know how girls feel?” Calliope is in her mother’s face.

“How couldn’t they feel that way? With everything you see on TV and the Internet.”

“You’re just a prude. What’s wrong with wanting to look good?” Calliope walks away from her mother and pulls at hangers, causing stiff magenta bras to tumble to the floor. Bea regrets her comment, realizing she was in her normal mode and not watching her tongue.

“I’m sorry, Calliope. You’re right. Of course you want to look good.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” Calliope shoves the fallen bras back on the metal rack.

Bea knows silence is best and clams up. She will guard her mouth. She will only speak when spoken to. She will agree with all Calliope says. She places an elbow on the edge of a rack, a rack she not so long ago clawed through, looking for the sexiest, and when none were sexy enough, she went to Lovers, bought pasties and a dildo, went home and watched porn for the first time, shaved her pubic hair when she realized this is what men want: a performance. She had no idea. She had to switch her mindset to a new channel. She had been living in a fantasy, thinking simple lovemaking was enough. Calliope was right, and she was wrong. How could she try to make her daughter believe what she no longer believed? Wasn’t Todd receptive? Didn’t he moan and tell her she was so fucking hot? Didn’t she walk into the bathroom after they had sex, as the semen dripped into the toilet, and think she had won? That she got him? Didn’t she at first think, as she applied dark purple eye-shadow and liquid, black eyeliner, that she looked like a transvestite, but when Todd saw her, didn’t his penis rise to the ceiling? Porn stars didn’t exit bathrooms like she used to, with a dusting of eye shadow, a little mascara, a romantic kimono. Men don’t want that, obviously. The simpler time is dead. Bea is sure she had been living in a fantasy alone, and now it is too hard to be alone—like a Twilight Zone episode. Walking through a desolate wasteland on another planet. Her daughter is clearly residing in reality on planet Earth. How could Bea blame her for that?

the bookstore

Common ground. Bea and Calliope walk through the wooden and glass doors and enter the temperate haven. A mound of fat, new books greets them, which comforts them both, but both walk by the display without stopping, first together, then apart. Calliope heads to teen novels and Bea to grownup ones. Bea doesn’t want to know what Calliope reads. When Calliope was young, Bea fed her Anne of Green Gables and Pippi Longstocking. Now the heroines, Bea is sure, are girls like Calliope, and Bea admits to herself as she looks blankly at the hard covers in the new-fiction aisle, that she doesn’t like Calliope. Calliope would not have been her friend if they were the same age. Teenage Bea liked shy girls, misfits, ones who made merry by talking about boys, not fucking them. Bea mentioned her worries to Todd, but unlike the fathers of old, who glared at their daughters’ boyfriends, Todd gave post-post-modern responses to Bea. We live in a highly-sexualized age. She’s a teenager. That’s what teenagers do. More confirmation that Bea was living on some other planet that only she inhabited.

Bea exhales and picks up a book. She likes the cover because it is beautiful, sad, literary. It is not a best-seller, and it never will be.

“Hey, Mom? Would it be okay if I get this?” Calliope startles Bea, no trace of lost innocence, no trace that she touched a boy’s penis. Just cautious brown eyes, asking without entitlement, asking for this book only because Bea had said today she could have anything she wants. Bea forgot about this character trait. Forgot that to this day and always, Calliope has taken the smaller piece of cake, waited until others grabbed the London Broil from the platter. Bea noticed this as the years went by and had to urge her daughter to take more.

“Of course you can, Sweetheart!” Bea melts, wraps her arms around her while she can, while Calliope is accepting affection. “Is there another book you want? Are you sure?” Bea searches her daughter’s eyes desperately for an inkling that such desire exists but can’t make it out, isn’t sure, wishes she knew the truth.

“No. Just this.” Calliope states, and Bea nods, saddened that she doesn’t want more.

Bea puts her book back on the shelf. There will be no time to read.

ghandi’s

In the car, Bea says, “absolutely anywhere.” Calliope chooses Indian. Bea will not argue this evening. She will acquiesce. She will listen. She will try to keep awe and remorse out of her eyes. She wants this to end perfectly and for their last mother-and-daughter moments to be blissful. She has learned that life spins on a dime, that tomorrow holds no promises, that trust is an illusion. This year: when everything unraveled, when her husband’s cock turned rancid in a foreign vagina, and when a foreign, young cock entered her daughter. The year of Bea’s awakening. The year when everything that she thought, wasn’t. She learned so much. She feels much like a molested child, innocence stolen, or like Adam, who ate the apple, whose eyes were then open, who then knew.

“Can I get a mango lassi?” Calliope is pure honey. Her eyes are huge and velvety brown. Her lashes sweep up and almost graze her arched, tweezed brows. Her cheeks are flushed; her lips, moist. What boy could resist her was never the question. The question was, why couldn’t she resist, for at least a little while?

“Of course you can, Sweetheart. You can have whatever you want. This is our day, remember?” Bea doesn’t want to sound dramatic or that doom impends, but she does want the day to feel extra special. She does want it memorable, something to hold onto.

Calliope jiggles in her seat, happy, happy. They decide what they want. Chicken Makhani, Bea’s favorite, and Malai Kofta, and Calliope chooses something different, something she’s never chosen.

“And Palaka soup.”

“Really?” This decision startles Bea. She reads the menu. “But it’s made with spinach?”

“I know. But it looks good. I want to try it.”

“Oh.” Bea is surprised. This is the girl who would not touch a green item on her plate, who tucked broccoli in the crevices of the underside of the table, and who nowadays simply leaves it on her plate, too old to be admonished. Bea gulps water and blinks, choking back what other changes she will miss.

But she makes nothing of it, as she promised herself. This is a day in which she accepts all her daughter offers.

Papadum is served while they wait for their entrées, and as Bea smashes the paper-thin wafer in her mouth without effort, the peppery heat feels like an omen—the bitter herbs, the blood on the door. Preparation. Protection. One’s firstborn.

Bea swallows the airy cracker, which feels as heavy as dough in her throat. Unzipping the side pocket of her purse, she reaches inside and lets her hand rest on the one item it contains. She bites her lip and gazes at Calliope who is spooning an emerald-green condiment carefully onto her Papadum.

“I have something for you,” Bea places the gift on the table.

Calliope looks up and in so doing, drops the condiment onto the stiff white tablecloth, causing herself to fret. She scoops the dark condiment with her spoon and places it on her small plate, but the smear on the cloth is unbecoming. She glances to the package, and her brow knits. Her mother has caused a collision as she often does; she has given a gift and a problem simultaneously. This Beatrice sees clearly only now. Bea sees before her a stream of such instances: an invitation to her small daughter to help her cook, then getting mad when the egg falls to the floor; French-braiding her hair, then scowling and yanking at the slipperiness of it; teaching Calliope about the birds and the bees by handing her a book and walking away.

“I’m sorry, honey. Don’t worry about it. They know how to get out stains.”

Calliope is receptive and restrained because of the small package on the table; surely, she can’t bark at her mother in this scenario. Bea slides the condiment trivet over the stain.

“What’s this for?” Calliope holds the beautifully wrapped box, soft paper in Calliope’s favorite color, blue.

“I told you I wanted a nice day with you. Inside this box is all that matters.”

Calliope opens the package without tearing the paper, pulling the tape away, one millimeter at a time. Inside the paper is an even more beautiful box made of blue velvet. Calliope opens it, anticipation clouding into confusion.

“It’s empty.” Calliope says.

“Yes. It’s empty. Because all that matters, you already have. It’s inside of you. It may sound corny, but it’s true.” Bea looks down, then up, straight at her daughter. “Don’t look for happiness from anyone else because people will disappoint you again and again. This little box is a reminder that all that matters, you have. No one can give it to you.”

Calliope nods, and in this nod, Bea realizes that she has done it again. She both soothes and cuts. Bea wishes it wasn’t so, but it seems it must be.

holy thursday

They are home now, and they go their separate ways, Calliope into her room and Beatrice into hers. They pass the boys on their way upstairs. Atlas is on the X-Box and plays games full of violence and gore, though he is only ten. Paras is on the computer in the family room where he toggles between Facebook, dark comics and a violent, interactive game. It is summer, and they will be in front of the screens for hours. Beatrice gave up on corralling them when the betrayal began, when her mind began to slip, when she had no strength for more than just placing rice and carrot sticks on plates. Now, she still doesn’t do much more. She tried, but when she realized that all turns to dust, that her good intentions bear bruised fruit that will rot, she gave up. The world is not hers. She does not understand it. She will let the youngest play on the screen until ten o’clock, then, as she touches his cheek and soft chin, she will tell him to brush his teeth, to get ready for bed. She’d let him stay up later, but that would get in the way of her performance with Todd.

Beatrice enters her bedroom, and as she expects, Todd lies on the bed with his smartphone. It would be odd to see him elsewhere. There is no activity from him at home beyond that which comes from the screen, though he will cook for the kids if asked. And he will do it without complaint. Bea has often thought that it is easy to happily cook for people when it is just once or twice a week, when it isn’t on your mind. And when he does, don’t they come running! Don’t they love when their father tunes in!

“Did the boys eat?”

“What I did was, I took the pork and cut it into strips, and I took lime, soy sauce and oyster sauce and made fajitas.” Todd is jovial, matter-of-fact.

“Yum.”

“How was dinner with Cal?” Todd speaks with politeness, as is his default, which Beatrice doesn’t trust anymore. He looks up from his screen for only a moment. This act alone makes Beatrice want to evaporate, but she forces out a response.

“It was nice. I think it made her happy. At least for a day.” Bea removes her earrings and places them in a small wooden box that Todd gave her before they were married. It is one of many gifts that carries with it a history. This gift belonged to his grandmother. As Beatrice closes the lid, she is aware of the incongruity, yet again, of everything she believed and everything she learned to be true. Everything fades. There is no real meaning in small, brown boxes. It is an illusion.

Bea glances at Todd as she heads out of the bedroom. He is unaware that the sight of him on the bed with his electronic device holds all the hopelessness in the world.

Down the stairs, she plods without sound. Even today, even so close to the end, she can’t help but check on things, make sure there is some semblance of order. There Atlas sits, her youngest, holding his controller, manipulating the fantasy on the screen. The back of his sweet head alone could bring her to her knees, but she keeps steady the thought that it’s only temporary. His head will grow, and if given the chance, in a couple of years, he would give her the back of it. He would not offer his milky cheeks or smiling gaze. He would be like his older brother.

In the kitchen, dishes are everywhere. That is the way with Todd—a delicious meal, but Bea cleans up twice as much. She is the maid. In the past, this brought her much grieving. For years, she did every task in the house. After the affair cracked open, Todd went to therapy and discovered he had ADHD. Bea hadn’t believed in ADHD, thought it was a label to give boys for being boys. But now she believes. Todd has ADHD and because of this, he is scattered, can’t focus, is in his own mind, and the smallest task is monumental. Hence, the kitchen remains dirty. Cooking is fun, but to wipe down a counter, to put away the sauce, is torture. If done, the ADHD literature tells the wife she is to praise the husband because for most of his life, he simply thought he was lazy. The supportive wife must encourage.

As Bea ties an apron around her waist, as she scrapes dishes into the trash, the ADHD spiral floods her again. As she traces the chain of events that led to her demise, she concludes that Todd fucked his girlfriend because he has ADHD. Todd needs new things to keep him interested. Bea grits her teeth while scrubbing a pan as she recalls that Todd’s girlfriend told him how amazing he was, how smart and sexy and funny. Todd told Bea that flattery was a big part of it. Bea’s fingers tear through the scrubby as she thinks of this, as she recalls his glow when leaving the house, as she recalls that Todd could look into Bea’s eyes of twenty years, eyes glassy with fear, that he could look upon her protruding collarbone from loss of appetite, that he could say without flinching, “You’re imagining things.”

Bea’s wrist burns as she lifts the cast-iron pan into the strainer. She wipes down the counter, finishes up in the kitchen and tucks in Atlas. She pushes his silky hair away from his soft forehead. He smiles. Though this isn’t his special day, she can’t help but lie down next to him for two minutes. She could sleep next to him easily, and considers it, but feels obligated to sleep with Todd, which perturbs her as she thinks it. All that is good is next to her in this bed. Innocence is the only thing left, the only thing she actually does believe in, but because it is fleeting, because innocence is not a permanent state, she lets that attachment go too, though it hurts, and she allows herself to rise from his bed. As she pulls the blanket up to his chin, she thinks God had it wrong: Human beings should be born old and then quickly make their way to childhood.

But God has disappointed her in lots of ways. She now knows that God—if there is one—is indifferent to her and all that she does.

This is her newfound theology: God doesn’t care.

Back in her room, Beatrice easily brings items to her bathroom without Todd noticing. Here it is: The countdown. Night One. Thursday. In the shower, she lets hot water blast over her. She shaves everything, even the soft fuzz that used to reside near her anus. It is gone forever and is now replaced with stubble that she removes right away. Bea is a goddess of the technological age. She is almost plastic.

When clean and soft, she steps out of the tub. Tonight is the color red. The outfit is cherry mesh from head to toe, opened at the crotch and ass. Something new for each of these last three nights. He will never forget. Glistening red lips to match. Black liquid eyeliner. And something else new: Bea has appropriated her daughter’s hair iron, and for the first time, she straightens her long, curly, dark hair. Not that she looks better this way—she, at least, believes she doesn’t. But who knows? Maybe she does. She has decided she knows nothing, that everything is upside down, that white is black, that the sun is the moon. So, she straightens. She glides the wand down slowly, first adding a shiny protectant. Yes, it is straight. She is now like all the young females. This must be what he wants. She is mystified by her transformation as she drags the wand down more and more. She is sure he will like it because so far every change she has made he says, Yes. More. I like it. Nice. She is no longer herself. She is buried and doesn’t matter. Whatever illusion she chooses will kill her so she chooses this one. The old one did not serve her well at all—she was betrayed by husband, children, and God.

From the top shelf of the medicine cabinet she pulls out white shimmer powder, something else new—only for tonight—and dusts her eyes, lips and ass. She is a fantasy with which no one can compete. He has said as much. She has smirked in the dim light. And soon, she will go out with a bang. She tosses the new powder in the trash.

Twisting in front of the mirror, she is satisfied. She pushes her shoulders back and opens the bathroom door, stepping into the bedroom.

“Well, well,” He says, through a fake smile. She knows only this smile these days, so she lets it come and go without letting it crumble her. What bothers her more is that he doesn’t react to her glory like she thinks he should. She thinks he should react like a teenage boy seeing a photo of breasts for the first time. His mouth should hang open; his eyes should pop out of his head. Instead, Todd gives the squinty-eyed smile. Well, well. As if all she did was rub her hand over his penis while wearing sweats. And of course, even now, his eyes move back to his screen—to close his browser with plenty of calm, taking the time to shut it down properly. The screen holds everything, constant movements, constant distractions—while Bea moves slower than an app. And her performances are not brand new anymore, no matter how they vary. Bea is still Bea.

With composure, he scoots over to her, able to focus now, and gains interest. He rubs her thigh, fingers her clit, moans. “I’ll be right back.” He goes to the bathroom and returns un-showered. A chair is next to the bed, and she is on it, legs apart. She learned, only after the affair, only after three children and a life lived together, that he doesn’t want to initiate. He wants to be gone after. She had attributed his passivity to him being a man of the mind. The truth is, the smuttier, the better—but she is to make the moves. That was, after all, what finally happened with his girlfriend. After the flattery, she simply unbuckled his belt. That was where the excitement lay—in the unbuckling.

So Bea pushes a big, shiny, purple dildo in her vagina for her husband’s viewing pleasure. Even though she knows the ultimate pleasure is her mouth on him—no matter what she looks like—she refuses not to show off all that she has, and, ultimately, all that he doesn’t have. She feels she is in total control. As she moans and lets her head drop back, as her husband pulls his shorts off, sweating, and rubbing his shaft, she understands the female performer. This is what men want—nothing else, no matter what they say.

“I’m sweating. God, I’m sweating,” Todd says, pulling at himself. “You are so beautiful. You are amazing. You are the most beautiful woman in the world.” His face contorts. “I’m so sorry.” Regret overtakes his lust, and he leans forward on the bed, his face now in the mattress. “I’m so sorry.”

Bea says nothing and waits for him to look up. She bats her eyelashes, sticks two fingers in her mouth, runs them up her labia, brings him back to the world of desire with her power, places his apology on a shelf with the others, trinkets too painful to dust. She mustn’t let mere apologies carry any more weight than what they are: passing feelings that will burn away in the colorful movement of an app or the newness of a different, adoring smile.

atlas in the morning

“Good morning, Mom.” Atlas is by Bea’s bed, excited about their day together.

“Hey, Muffin,” Bea says, waking at the sound of his soft plea, and reaching for him, gently pulling his head down to her chest. He folds his limber legs and hugs her easily. “What time is it?” she asks, reaching for the clock.

He lifts his head and turns the clock for her.

“Six-thirty?” She widens her eyes.

“I wanted to give you time to get ready.” He looks at her with the wisdom he carries, wisdom he shouldn’t possess at age ten.

“It doesn’t take me that long. The stores won’t open until nine.”

“I know.” He shrugs, not letting on to his true motives.

But Bea knows. He is afraid she will make him wait and wait, that she will close her bedroom door to smoke cigarettes, to stare out the window, to blank out and leave him wanting. But that won’t happen. There will be nomore of that. There is no time.

“I will get right up. I promise. Now you go and scrub those teeth and put on your jeans without holes in the knees.”

“Got it.” He bounces out, happy for the firm, motherly direction, not the distant, hazy woman who took her place this past year.

Bea waits until he is clearly out the door to get up since these days she sleeps nude. It is Friday morning, and Todd is a weight beside her, having stayed up on his phone as usual, right after sex. Sex interrupts phone time. There is little post-coital chit-chat. Bea had not been finding this habit hurtful because it was just part of the routine, but when it dawned on her that it was expected and acceptable behavior, that he would reach for the phone two minutes after he pulled out of her, that if she didn’t begin a conversation, then one wouldn’t happen, it was just more confirmation that it was over.

Bea pulls back the covers, walks to the bathroom where semen drips onto the floor. She looks in the mirror to see her makeup still there, but less of it. It has taken on a bruised look, her eyes stained and heavy, the weight of dark secrets.

After her shower, Beatrice leaves the bathroom in a robe to find Todd on his back, staring up at his phone, his thumbs busy. He glances at her for a micro-moment.

“Hi, Sweetie.”

“Hi,” she says, breathy with resignation.

She gets dressed, puts on fresh makeup, and heads out the door with her youngest without saying goodbye.

Her babe! At ten, he is her sunshine! His pouts are nothing but water that fall to the ground, drying in an instant. Poor Atlas, who has endured the screams of his siblings. The unfairness! His brother and sister did not endure such wrath! Oh, no! They were protected from the vulgarities of the world. Poor Atlas—to be swept into knowing before his time.

In the car, she looks in her review mirror at his beautiful, wise eyes and almost runs the car off the road.

“Ah!” Bea exclaims, then laughs as is her way right after all her many near-misses. “I’m sorry, Muffin!”

Atlas adjusts himself, feels his seatbelt. “It’s okay.”

His voice sounds deeper than usual, and she swallows away the crackling she’ll miss in a few years, the way Paras’s voice crackled only months ago. But she’ll also miss the cold shoulders. She takes a deep breath.

“Did you even notice that I didn’t offer you breakfast before we left?”

“Come to think of it, no. No, I didn’t.” Atlas’s response carries a lilt, a sing-song-y timbre, a response Bea treasures because this is the lilt of children in storybooks of yesteryear, of children who are composed when necessary, of children who are imaginative and thoughtful, of Mille-Mollie-Mandy and Winnie-the-Pooh, the lilt of her children before they grow up. Bea closes her eyes for a moment.

“Well. I had a reason. It’s because we’re going to eat breakfast at a restaurant, just you and me.”

“Cool,” he says.

Through the rearview mirror, she sees him looking straight ahead, wearing a soft smile. She has given him a nice surprise. She is struck by their time together, now, and the few times they have been alone, just the two of them. It has always been calming. It is a time when his older brother and sister cannot call him names, cannot build their self-confidence by lowering his. Bea bites her thumbnail because she is unsure if there is great sadness inside Atlas that she doesn’t detect, that she is afraid to detect, afraid one day that he will burst out in a howl. But now, as he scans the buildings they pass, she detects only strength. He has seen it all—well, almost all. She tried to shield him from the terrible nights with Todd. She has an inkling that he knows some of it but just doesn’t say. Just like he knows she is smoking but says nothing. Smoking, out of the blue, from this strange new mother who doesn’t look like the other mothers who volunteer at school—not any more. This woman who took the place of his mom, who now wears tight little shirts and eye-shadow. But to Altas, these days, she gives her all when she can. She doesn’t want to be a ghost to him anymore, as she was for a year, though he will accept her in all her forms. He will not be embarrassed by her because he is still a real, whole boy, not yet a confused halfling, a teenager.

Yes, she is struck again and again by her time with him and how she hasn’t had enough of it. Oh, the heaviness of his goodness. She remembers, as she drives with her quiet boy, how he assuaged her when Todd was out night after night, how together she and Atlas learned new songs on YouTube, how they sung them together in each other’s faces, how they laughed, how there was no apprehension. That was the great soothing balm. There really could be nothing better than that, she thinks, as she is at a stoplight and watches her Atlas—actually turning around to study his face, to soak it in. Those moments they shared should be frozen in time, like a fly in amber, for others to walk around, to stare into, intent on the human-size amber rock of which Atlas and Beatrice are embedded, as they sing into each other’s faces, forever. Amazing. They will say. They got trapped inside while alive.

Into the parking lot, they pull. A restaurant they’ve only been to once, all of them together as a family. A hometown atmosphere with tall pies and chubby waitresses.

“Yes!” Atlas says.

“I knew you’d love it.” Bea turns off the car. “Let’s go in.”

Once inside, the mirrors and angles are disconcerting, which makes the escorting of the waitress and the grid of the booths that much more comforting. She places two big plastic menus and a kids’ menu in front of them.

“Someone will be right with you.” The waitress smiles and leaves.

“Forget the kiddie menu today.” Bea pushes the flimsy paper to the side, an out-of-character action that causes a flicker of light to emerge from Atlas’s otherwise placid gaze. From habit, Beatrice squares and opens the big menu in front of Altas, and even as she does it, she realizes it is not necessary. He is a bigger boy than she even knows or wants to know. She watches his eyes scan the overwhelming options and is happy she can do something for him.

“They serve any of it all the time. If you want steak at nine in the morning, they’ll make it for you.”

“I want one of these.” He points to a giant waffle with strawberries and whip cream.

“It’s yours.” She loves his choice. Strawberries have always been his favorite, and fruit is healthy.

“And bacon.” He points to a full order.

“Can you eat all that?”

“Maybe you’re right. I’ll just have the waffle.” He nods.

“Are you sure?”

He smiles at her, but in that smile she sees that this is an answer to please her and not him.

“Atlas,” She places her hand on his. “It would please me most if you get all that you want. That would make me the happiest.”

“Okay. I’ll get the bacon.” He relaxes.

She beams.

“And remember. It isn’t your job to make everyone happy. It’s okay for you to stick your tongue out to the world.” At that, she lets some of her old silliness take over, the silliness she had for all of them, but which almost died this year, though it still pushes its way to the forefront, sickly, with a raspy voice, at times. “So when the waitress comes, if you don’t like the sight of her, you just stick out your tongue.”

With this, he bursts out laughing, still in tune with his Mama, still not ready to cross over and join the others.

The waitress arrives at their booth. “I’m Anne, and I’ll be your waitress today. What can I get you?”

Both Altas and Bea order through laughter as the waitress scowls, both imagining the unimaginable, both knowing the other is thinking the same thought.

the dead shall live

After breakfast, Bea leaves a big tip and ushers her babe out the door, more content than she can remember feeling. He is perfectly happy in her presence. She breathes in deeply as he stands by the car door, waiting like a good boy. She unlocks it from her side and when he opens the back door, she says, “get in the front.”

“Really?”

“Yes. Just for today.”

He slams the back door and gets in front. Buckles up, touches his surroundings—opens the glove compartment, reaches for the radio.

“Go ahead. You choose.”

He has watched his siblings from the back long enough to know what button causes what effect. He has nothing to learn; he knows already.

He presses the pre-set stations programmed by Calliope. Eminem comes on, a dance favorite of theirs, a song that in the past Beatrice would have changed because of the lyrics, but not anymore. Now, she listens to the kids instead of the other way around. Her experience tells her that guarding their purity has the opposite effect.

They both dance as they ride. Bea turns up the volume. Bea only realized the lyrics to this particular song recently—lyrics about “cum on tits”—after dancing hard to them many times. Now that she knows the lyrics, and Atlas knows that she knows the lyrics, it’s no use to pretend. They don’t actually sing these particular words—they both know better—but they feel free and rebellious and a little naughty as they bob in their seats.

“First stop: GamePlay,” Bea says as they head toward the next strip mall.

“Yes!” he says, making a fist.

Inside the video game store, Atlas is the master. At some point in video game production, Bea stopped processing. She isn’t even sure if they are called video games. It doesn’t matter; Atlas knows. He has been an attentive student, his brother bossing him around and Atlas complying. Beatrice has felt powerless as she has watched this dynamic. When does brotherly worship become willing submission to abuse?

Now, alongside Atlas, she will be the puppet, he the puppeteer.

“Is there one you’ve been wanting?” She sidles up beside him but gives him space.

“I want Halo, but Paras said it’s lame.” Atlas pulls the hood of his sweatshirt over his head.

“If it’s not lame to you, that’s what matters.”

Atlas yanks his hood further down over his forehead. Bea crosses her arms in front of her. “Do you know that it would be perfectly fine if you walked in the house, took out Halo, and began to play it while Paras complained the whole time?”

Atlas shrugs.

“Even if he cried, it would still be perfectly fine.”

“Paras wouldn’t cry.” Atlas tugs off his hood.

“No, he wouldn’t. But he might try to make you feel bad about your choice. He might do that.” Bea gazes at the blur of games on the wall. “I wonder why he does that.”

“I know why he does it.” Atlas states, grabbing Halo 1, 2 and 3 from the wall.

“You do?” Beatrice is surprised. “Why?”

“He does it because it makes him feel better. He doesn’t feel so good about himself.” He looks down and shakes his head in genuine pity. “I don’t mind.” He looks up at Bea with a look that says he really has no other choice.

“Well, I mind. You’re not his punching bag.”

“It’s not like that, Mom,” Atlas says. This has been the way lately, where Beatrice jumps to the defense of one sibling only to be told that she is wrong, that there is no problem, that her perspective is off. That she understands nothing.

“Pick another game. Whatever you want.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

The electronic doorbell sounds through GamePlay and in walk Todd and Paras, smiling and joking as they enter. Their presence both elates and jumbles Bea. It has been so rare these days when they are all together, or almost all.

“Why are you here?” she asks, breathless.

“I told Paras I’d buy him a game.” Buying has always been Todd’s way of bonding.

Paras grabs a Halo game from Atlas’s hand. “Ha!” he says. “What a loser.”

Beatrice glares. “Paras, come with me.” When Paras doesn’t budge, she raises her voice, knowing it will embarrass him and make him obey. She walks to the car, and he follows. “Get in. We need to talk.”

Paras gets in and slumps.

“Why are you so mean to your brother?”

“He just acts so cool.” Paras mumbles.

“He’s ten years old. How cool could he be acting?” Bea asks. “You put him down. You put down his choices. It’s got to weigh on him after a while.”

“He can handle it. Nothing bothers him.”

Paras is motionless, and Bea is hit by this fact. She is not usually side-by-side with her teenage son. Bea thinks his teenage body should be brimming with boy energy, but his presence is airy and still, like he could disappear in front of her eyes. His hands are curved upward and pale, resting on his thighs that look thin under his baggy shorts. And when Bea looks at his face, she sees shadows under his eyes and in his eyes. Bea knows this face, this face that is just like hers, this face that senses too much, that taps into the sadness all around. She knows that Paras isn’t good at carrying the burdens of the malformed world like his brother. Once, as a teary-eyed little boy, he brought a dead frog from the street to the kitchen counter. He grieved for its broken body, had lamented that the frog’s legs were made to hop but wouldn’t hop anymore. Little Paras lay on the sofa for hours, the tiny corpse below him on the rug. Last year, night after night, Paras asked his spacey-eyed mother where his father was. When Bea’s excuses turned to shrugs, Paras stopped asking, and he stopped eating, too, just like Bea, and soon the both of them resorted to their bedrooms, both curled on their sides.

Bea glances at Gameplay’s façade and through the glass, she sees Atlas acting out a scenario of one of the games to show his father. Atlas sweeps the air with an invisible gun, destroying the evil that surrounds him. Atlas sweeps and sweeps.

Bea turns toward Paras who is inert, lifeless. “You know,” Bea says, “it’s okay to feel pain.”

Paras’s mouth opens, and his lips appear swollen as they tremble, as if his agony has gathered there, in that spot. “Sometimes,” his voice crackles, “if I didn’t think there was a hell, I would just—” he doesn’t finish his words.

Bea’s lips quiver, too, now, as she watches her son’s chest rise and fall. His words burn because what keeps him holding on to life is fear, but Bea knows there is no Hell and there is no Heaven, that Heaven and Hell are right here, though she cannot state this truth to her son. His illusion is keeping him alive.

“You know what, Paras? Things are going to get better. You’ll see.”

“Yeah?” He looks at her. “What makes you so sure?”

“Because you are such a great person that it just has to. The world needs Paras.”

“I don’t know if I can do it,” He chokes out.

Bea reaches to touch his hair, ever so slightly, not how she wants to because she knows that would be too much—he would pull away—but just to touch him a little, just to feel the soft hair on the tips of her fingers. Her hand shakes as it extends toward her son, a hand so skinny these days that she can see each vein and tendon. But Paras doesn’t move. He doesn’t flinch, so she smoothes his hair more, and she smoothes his head, too, and she weeps silently, her arm reaching across, barely able to hold itself up, burning, as she strokes and strokes.

Thea Swanson holds an MFA in Writing from Pacific University in Oregon. Her independentlypublished novel,The Curious Solitude of Anise, received excellent reviews from Kirkus, Switchback and others. Thea’s stories can be found in Anemone Sidecar, Camera Obscura, Crab Creek Review, Danse Macabre, Dark Matter Journal, Dirty Chai, Image, New Plains Review, Our Stories, The Sonder Review and forthcoming in Black Denim Lit, Fiction Southeast, Toad Suck Review, Gone Lawn, and Your Impossible Voice. Thea has taught English from middle school to college, but she can’t afford to teach anymore, so she does other things.