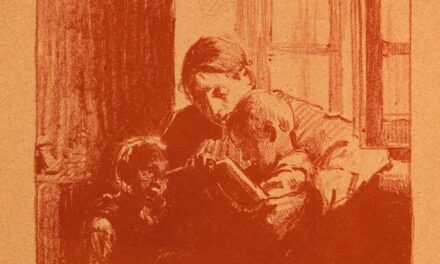

Bird-Man Pendant. c. 700–1550, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The House God of Hotel Eldorado

by Jay Merill

Naira wrings out her wiping cloth and hangs it over the rail. Behind her, through the doorway, she hears the sound of wailing. She has been housemaid at the Hotel Eldorado for some months. And, though there are frequent ups and downs with the daily bickering between Guadalupe and her husband Dezi, this is the first time Naira has heard Guadalupe, her mistress and proprietor of the Hotel, cry out in such distress. It is because the small gold figurine which stood on the hall table is missing. Naira has always found the bird-like statue scary. She does not like the way it sits perched on a flat wide knife, or how the curved wings creep up the sides of its face pointing to round bird-like eyes that stare into you no matter where you stand facing it.

Naira noticed the figurine was missing yesterday as she wiped dust from the window ledge in the hall. She had looked down, following the direction of her hand along the window pane and seen that the table beneath the window was empty. For a moment she had felt happy; she wouldn’t have to see the ugly frightening statue, and now she wouldn’t have to dust it either. But then she felt afraid and dreaded having to tell Guadalupe. For a moment, Naira thought maybe Guadalupe had removed it for some reason. After all, she was a woman with occasional unexplained whims. But if Guadalupe had not removed the thing and if Naira did not tell her mistress it was missing, this would only throw suspicion on her. Naira did not want any trouble. This was not a bad job and she needed to hang onto it. Of course, if Guadalupe wasn’t aware the statue was gone, Naira would be the one to suffer for being the bearer of such evil tidings. Either way there was no way out. So she went to the little dark room at the back of the hotel which served as Guadalupe’s office, and with many misgivings knocked on the door.

When Naira entered, Guadalupe was going through her accounts in a big book, sighing with a look of concentration on her face just as though there had been no knock in the first place, as though she had not just called ‘Come in,’ and as though Naira was not standing there in the room with a duster in one hand and a can of cleaning spray in the other. Naira had looked round uneasily because it can be unnerving when somebody acts as though you don’t exist. She shuffled and then coughed, glanced down and caught sight of her own two feet. This was reassuring. She was standing here. She was clearly visible. It irritated her to be made to feel otherwise. And maybe more to punish Guadalupe for this transgression than from any fear of consequences, Naira yelled out sharply, ‘The gold statuette in the hall has gone. It is nowhere to be seen. Have you removed it, please?’ Despite her fears of being the messenger, Naira felt a certain thrill at the words. There was a tinge of satisfaction when Guadalupe, her face gone green and prickly as a pear, leapt from her chair and screamed, ‘My precious Tumi!’ Naira then dutifully offered to look for the missing treasure, anticipating this would mean extra work—delving pointlessly into rarely used cupboards and searching through the boxes on the porch, even scouring the ramshackle sheds in the garden. Though the old hotel could have done with some repairs and a fresh coat of paint, it was reasonably well-kept but for some outhouses out the back which were run down and Naira did not relish entering them. But she was spared this by Guadalupe’s next remark:

‘No, you don’t. I won’t have you hunting for my figurine.’

Naira was relieved though stung by Guadalupe’s ungracious reply.

Two days have gone by and Naira wishes she could go away somewhere for, as she had predicted, she is the main one who receives Guadalupe’s wrath over the missing gold figure. When she goes to change the bed linen from Guadalupe’s bed, Naira sees her mistress’s fancy soaps and other expensive toiletries lying strewn on the floor. She picks them up hastily but the gold weave string bag where they are kept and which hangs from the handle of Guadalupe’s bathroom door is not there. Fearing further trouble, Naira puts the items into a drawer and prays Guadalupe will not think to look for them until after the current turbulence has passed.

One good thing is that Guadalupe’s husband, Dezi, is back today from Cusco where he’s been for the last couple of days ordering provisions. Naira hopes that his presence will deflect Guadalupe’s misery away from herself. Since her arrival, Naira has noticed that whether good or bad things happen, Guadalupe and Dezi reflect them on one another. So, when a week’s worth of beaded purses were sold in one afternoon for a good price to a collector, Guadalupe made Dezi his favourite dinner of fish stew; when a stray fox ran into the garden at night and chewed off the flowers of the best hibiscus bush, Guadalupe brought Dezi the old green tea he did not like, instead of sharing with him the chicha that had been handed round that evening to guests. When the hinge of the gate broke, and Dezi had to spend the morning fixing it instead of relaxing over his breakfast, he later that night refused to go to bed and sat up instead with a glass of rum. But when some visitors at the hotel gave Dezi a big tip for sorting out the brakes of their car, Guadalupe received breakfast in bed the following morning. With Dezi’s return, Naira’s hopes are answered. The moment Dezi’s head is seen through the glass panes of the hotel door that afternoon, Guadalupe is ready in the hall to tick him off about something or about nothing, just to relieve her feelings.

Guadalupe has kept to her room for most of the day. When she comes out in the evening to sit down with the hotel guests at the long table in the foyer, her eyes are red. She ignores Naira. Naira is tired from cleaning and cooking the meal they are about to eat, and running back and forth at the behest of Dezi to bring this or do that. By the time she gets to sit down and begin sewing bead purses for tomorrow’s stock, she feels quite ghostlike with fatigue and is almost prepared to believe she is invisible after all.

Although Guadalupe has left Naira alone since the arrival of Dezi, things are no better than before, for Dezi is full of complaints by proxy. It is Dezi who glares at her now, snarls when she approaches, and finds fault with every minute thing she has not done, or has not done well. Hotel guests, who have heard about the missing statuette, commiserate with Guadalupe in soothing tones and make helpful but ultimately useless suggestions as to how it may be recovered. They all drink chicha together, chatting in Spanish and English, and listening to the rush of the Urubamba River through the open window. Some equanimity is gained. Naira meantime, sits at the far end of the long table attaching the strings to the bead purses for the next day and can hardly conceal her yawns. Her mind harks back to a month ago—the most joyful period of her life. It was her sixteenth birthday though that was not what made her happy. The reason for the shine in her eyes was the arrival of Vancho, Guadalupe’s son from a previous marriage, on a week’s vacation from university. Each night after the chicha had been served and all had retired to their rooms, and as soon as the snoring of Guadalupe started up, signaling to them everything was safe, Vancho would come to Naira in her little bed in the recess off the hall. There was no second hotel assistant then so Naira had the small space to herself. Here, she and Vancho would talk and doze and make love all night, coiled together in sleep as well as out of it. Vancho would rise early the next morning with Naira, and go back to his room. A short while later, he would make a noisy exit, after rumpling the bedclothes. He would accompany Naira to her spot on the road to Machu Picchu and help her sell her wares to passing tourists. The love affair had to be kept from Guadalupe and Dezi, of course, but it was a time of great happiness for Naira. Before Vancho left to go back to university in Ica, they swore eternal love for one another. They both cried at the parting and prayed kneeling side by side to Our Lady of Mercy for a time when they could be together.

But since that wonderful week when Vancho was here, Naira thinks things have not been right with Guadalupe and she’s aware that her mistress has been sleepwalking. Two or three times in the past month Naira has peeked out from her curtained recess in the hall and seen Guadalupe gliding down the stairs in her nightgown, and on one occasion even passing into the garden. As for the statue, it had generated anxiety in her mistress long before it actually went missing. Naira had no idea whether the icon was made of real gold or not, but she knew that in Guadalupe’s mind it was of great value. Guadalupe had inherited the hotel from her great aunt Juanita and as far back as she could remember, Tumi had always been there. Naira once overheard her mistress telling one of the guests that if anyone were to gain possession of the relic, the hotel would pass to them, as whoever had the one also had the other; the two went together and could not be separated. Naira remembers thinking that if this were so, then wasn’t Guadalupe taking a big risk to leave it out in the open upon a table by a window where anyone would be able to take it if they were so dishonest? She put the carelessness down to her mistress’s vanity, a woman who loved nothing better than to demonstrate what she was worth, always getting up in expensive dresses and parading about in her jewelry and decorative hair combs.

The guests sit with their hosts as usual at the evening table. Guadalupe is subdued but congenial. Dezi keeps the talk going. His current topic is the quipu of the Inca and he asks whether anyone understands all that it was capable of recording. They’re not sure, and Dezi, of course, will tell them that it can be used for storing all sorts of information. He enjoys seeing their amazement that a cord with coloured threads and a series of knots can be of such importance. Naira sews and dreams, the hotel guests smile and look respectfully towards Dezi with his vast local knowledge. When an American guest finally asks a question about the quipu Dezi, suddenly switches themes and starts talking about the missing house god of the hotel. The name of the statue, he says, is Naylamp. He says it is an ancient bird deity that sits upon the tumi, or sacrificial knife. The guests show interest and say politely how they wish they might have seen it. Guadalupe goes at once to the sideboard for the chicha. Everyone toasts and drinks a glass or two. A guest picks up an American lifestyle magazine angled casually on the corner of the table and says, ‘Oh, there is a picture of the Hotel Eldorado on the front cover.’

Naira looks at the picture too, as she has done so many times before. She sees the photo of two girls who once worked here, standing in their native costumes in front of the hotel. They are Chaska, a girl who was here when Naira first came to the hotel but left shortly after to join her family in Cajamarca, and another girl, Pilar, whom Naira never met. The girls look spectacular in their woven jackets each with the traditional lliclla, and the k’eperina knotted just under the neck and hanging down the back of the shoulder. Both are wearing hats. Chaska looks lost in thought, Pilar has an enchanting smile. Naira wonders where both girls are now, just as she always does when she sees their image. Tonight, seated beside her is a young girl, Rita. She is a new assistant and this is her first day. Rita also looks at the picture, perhaps wondering what became of the girls in the photograph, and what their stories are. Guadalupe has said little or nothing through dinner. Her face is a mask and it is hard to know what she thinks, though Naira believes she must still be mourning the missing beloved house god. Dezi returns to the subject of the quipu, outlining its importance. Naira whispers to Rita to pay attention to what he says as he may stop at any moment and ask one of them a question. This alarms Rita, she is only fourteen years old and of a nervous disposition.

In the morning, Naira and Rita dress in clothes which are a mirror image of those worn by the girls in the picture. They go out early to catch the first of the tourists on their way to Machu Picchu and stand at their accustomed place at the base of the steep mountain path. Each holds up a tray strapped to their shoulders loaded with threaded purses and other handicrafts. They listen to the roar of the Urubamba River far below them.

On more than one occasion, Naira and Rita have seen Guadalupe stand at the window of the hotel foyer staring across to the hills on the far side of the river in a valley below. Naira knows that Guadalupe looks in that direction because a certain farmer lives in those hills. It is rumored that Guadalupe once had words with him over some second-rate maize that he tried to sell her. Since that time, there have been hostile looks between the two whenever they happen to cross paths in the village. Naira has overheard Guadalupe telling Dezi that she does not trust this farmer and Naira believes that Guadalupe now suspects the man of stealing the house god from the hotel. His chucra lies in the exact region where Guadalupe fixes her gaze.

When Rita and Naira come in from selling their handicrafts in the early afternoon, Guadalupe is again looking out the front window of the hotel and across the river uttering increasingly virulent oaths against the farmer. Only a few weeks ago while in the front garden, Naira had seen Guadalupe spit towards the river and hills. And she knew that this, too, was meant for the farmer. Guadalupe’s ill feeling has been mounting to a high-fevered pitch. Naira goes about her daily duties almost distracted wondering what will happen next.

After a few angry outbursts addressed to no one in particular, or at least to no one that Naira can see, Guadalupe becomes ominously silent. Naira no longer receives instructions about what needs to be done in the hotel, and has to decide on her own when to change the linens and put out fresh towels. Guadalupe says nothing about what she wishes to cook for dinner, and yet she used to be so extremely fussy. Naira has to devise all the menus herself. She now does all the cooking and she is left to give instructions to Rita and show the girl how everything should be done. Naira is constantly exhausted when she goes to bed. There is no longer time for lying awake in the dark and thinking dreamily about Vancho, her true love, whose memory remains deeply embedded in her heart.

Early one morning, after Dezi has returned from another of his trips to Cusco, Naira is fixing her native costume in preparation to sell the wares on the road up to Machu Picchu. Rita, who is already dressed and waiting for her, runs back to their hallway-room excited, saying she has seen Guadalupe rushing round the garden with a frying pan. Naira cannot believe this, since she has never seen Guadalupe up at this early hour before. But Rita insists it is true. Both girls run out the front door of the hotel to look about but find no sign of Guadalupe. They return to pick up their tray of wares when suddenly Dezi rushes past them pulling on his poncho as he goes, the morning air being fresh and a bit cold. The girls follow after him with their trays still strapped to them and walk across the garden on the way to the hill road. As they pass through the gate by the papaya bush, they both catch sight of Dezi in close pursuit of the fleeing Guadalupe. The two girls begin shaking with laughter but stop abruptly when they notice that Guadalupe has something in her hand which she holds high and waves about as she goes. But Naira sees that it is more like a small shovel than a frying pan. Guadalupe is brandishing the shovel like a knife, stabbing sharply into air, making a cutting and slicing motion, then waving it in a high arc over her head. Both Rita and Naira feel afraid. Rita frets about what sort of place this is. Naira tries to persuade Rita that things are not usually so strange, that Guadalupe is not really out of her mind. But, even Naira is having doubts, though she keeps them to herself.

After the incident, things at the hotel immediately settle down. Everything goes back to routine, to a normality Naira had thought was beyond them forever and that Rita had not believed existed. Guadalupe continues to nag and grumble her way through each day to no one in particular it seems, but redeems herself through little acts of kindness such as giving the girls some of the best fruit to eat when many, as Naira believes, wouldn’t have bothered to do so. Guadalupe returns to cooking the evening meal herself for staff and tourists alike and they all sit down together at the large table, the girls, guests and hosts, lingering over the chicha for an hour or more. Naira thinks Guadalupe, who has never been very talkative, is even quieter than usual. Lately, Dezi’s nightly informative talks are in danger of becoming rants. But by then, the guests have been mellowed by the chicha and are less inclined to notice. Naira, now relieved of the onerous cooking duties, has energy left at the end of each day to dream happily about Vancho’s kisses in bed before she sleeps, and imagines his return. But to believe things can be truly calm is only a false hope. She senses a storm about to break.

It is evening, though not yet dinnertime. Rita is in the garden bringing in the washing from the line. She hums a tune as she pulls the pegs from the rows of sheets and towels when she happens to see Guadalupe standing on the other side of the washing line. Guadalupe, as though to mirror the missing statue, is wearing the face mask of a giant bird with a huge beak and bright colours. Rita collapses into a billowing sheet in an effort to hide herself. She is too frightened to run away or call out to Naira who is only a short distance away hunched over dishes in the kitchen window above the garden. With all her might, Rita, burrowed in the sheet, wills Naira to raise her head. Guadalupe stares fixedly at the shape of Rita wound within the sheet, then raises her arms as if to fly and emits a sound that is half groan, half whistle. Rita wets herself. Naira, hearing the unfamiliar noise from the garden, finally looks up. She sees Guadalupe in the grotesque mask leaping upwards as if about to take off into the sky. She does not see Rita wrapped in the sheet, at first. Naira, a brave young woman, runs out into the garden and calls to her. She tries to avoid the fearful sight of Guadalupe armed with the shovel jumping up and falling back and prancing about the lawn with her arms extended. Dezi comes out, giving Naira the customary scowl as though Naira were to blame.

Dezi jumps up to snatch the shovel from Guadalupe’s hand, but she is taller and he cannot reach. Even with his highest leap, he only comes level with the top of her shoulder. Her arms are held high and she will not bring them down. Then Guadalupe takes off across the lawn with Dezi after her. They disappear down a sloping path behind a papaya bush. Shrill whistling sounds of a bird, mingled with shouts and cries, follow them. Once they are out of sight, Naira sees Rita and rushes to untangle her taut body from the sheet. They go indoors and wait. As the evening deepens, there is still no Guadalupe and Dezi. It is past dinner-time and nothing is prepared. Naira thinks she had better put something together quickly as the hotel guests have come back from Machu Picchu and are now in their rooms. Rita and Naira hear the sound of water splashing into the drain which means the guests are having their customary wash before coming downstairs for dinner. The light becomes dimmer and Naira takes one last look outside for Guadalupe and Dezi. Still, no sign of either either one. Later, while in the middle of preparing the corn for the guests, from the kitchen window, she glimpses a strange pale object swaying in the papaya bush. She tells Rita to go see what it is. Rita, however, is afraid it may be a ghost, and Naira can’t persuade her. After the food has been carried to the big table, Naira slips into the garden. All is still and sweet smelling. Naira approaches the bush and peers into the foliage. She is amazed to see it is Guadalupe’s gold weave toilet bag hanging on a branch. She gently extracts the loops from the twig wondering how long it has been there. It is heavy and she slackens the ribbons. When she looks inside she sees a shine of gold. The house god! Naira runs inside and with trembling hands, returns the figurine to the small table in the hall where it belongs. She turns the house god to face the door, knowing how delighted Guadalupe will be when she comes home and sees her cherished Tumi watching her. It will appear that he awaits her return. Naira delights in the thought of this.

After the evening meal is over, the guests retire early because Dezi is not there to give his nightly lecture. Rita and Naira sit in a state of hushed anxiety in the enclosed veranda facing the hotel garden. They keep watch. One, two, then three hours go by. Each chime of the clock feels like their own hearts pounding. An hour left to midnight and there is no thought of sleep. Naira glances back through the doorway into the hall, sees the house god glowing gold in the semi-darkness. She realises she no longer finds it ugly. The sight of it even gives some comfort and hope that things will be better.

By one in the morning, the girls are slumped exhausted in their chairs when they suddenly hear a commotion in the garden, loud voices in the night air presaged by a flood of lights. Police officers and others have arrived.

Through the combined accounts of neighbours and other witnesses given to police and medical officials, Naira and Rita soon found out what occurred just after Guadalupe and Dezi disappeared from view beyond the papaya bush. The couple had run towards the village. Discordant voices could be heard and neighbours looked out from their doorways and windows to see a strange woman in a face mask whom they all recognized to be Guadalupe. They saw Dezi too, with his poncho flying as he went after her. Tourists in the street also turned to stare. Villagers came out of their houses. Everyone claimed Guadalupe was cutting the air about her with some metallic looking object and that both ran down towards the old river road with one or two locals following out of curiosity. They kept running until they arrived at the lower reaches of the rocky ravine. Once at the bottom, the quarrel between the two grew louder. Those who had followed heard their angry shouts. Through the sparse bushes they saw Dezi leap into the air as if in a rage, then lose his footing and fall into the river. Guadalupe jumped in after him and tried to grasp his waving arm. The two spun round each other at first like two light hollow logs then floated downstream in the river’s fast swirl and, as neither were light or hollow, they sank. This report of Dezi’s accident and Guadalupe’s attempted rescue was verified by two alpaca herders and a farmer across the other side of the river. The men told of how the pair were swept away, their screams followed by silence. Rita and Naira are shocked and tearful and unable to believe it at first. Only gradually, as night passes to morning do they come to accept the horrific story as the truth.

Two months have passed since Guadalupe and Dezi were lost to the waters of the Urubamba River, their bodies not found. The Hotel Eldorado has remained closed, but will soon reopen after being renovated with an extension built to the rear of the building for more guest rooms.

It is a warm summer evening. After painting walls all afternoon, Naira sits resting on the veranda. Vancho stands on a small ladder nearby putting in place new tiles where the old ones had fallen off above the windows years ago. Naira and Vancho call happily to one another. Rita who has no family to return to is very attached to Naira, whom she finds soothing. It helps, too, that Naira has asked Rita to stay on as hotel assistant for when they reopen. Vancho and Naira will marry as soon as is decently permissible.

Naira is the new proprietor and now holds the very set of house keys that were once the proud possession of Guadalupe. Rita thinks how happy she is about these developments and feels secure knowing that Naira will be in charge. Vancho has bought a handsome glass-fronted cabinet for the greater glory of Naylamp. It felt like the right thing to do. He hopes it will smile on the hotel and offer them all protection. Vancho has heard the odd story of the figurine’s disappearance and its later discovery in the papaya bush but no one as yet feels enough nerve to come up with a feasible explanation. Sometimes, all three of them go tearfully to the Urubamba River and pray for the souls of those they have lost.

Fiction by Jay Merill is recently published or forthcoming in Apocrypha and Abstractions, Corium, Epiphany, Literary Orphans, Prairie Schooner, SmokeLong Quarterly, Wigleaf and other great publications. Jay has two short story collections published by Salt and was nominated for the Frank O’Connor Award. She is the winner of the Salt Short Story Prize. Jay lives in London and is Writer in Residence at Women in Publishing. @JayMerill