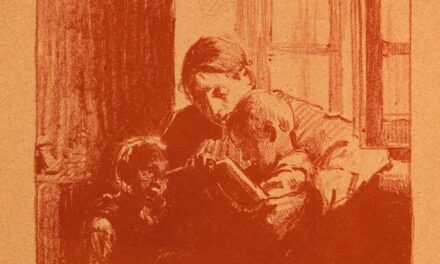

Washington Allston. Profile of a Girl’s Head with Braids. 1821 – 1828, Harvard Art Museums.

Ammi’s Birth, a memoir excerpt

by Neha Thakur

Father unfastened my locks a third time clutching me between his legs like a little sheep. “Don’t move,” he said bending over as though speculating planetary positions in the length of my mane. In his youth, he had trapped tigers, outrun wild dogs and dealt with armed men but now he struggled to put thirty inches of inanimate strands in place. After all, braiding a woman’s hair is no trivial feat.

After he was finished, he confessed he had never braided a woman’s hair before, not even Ammi’s. Then he left to fetch Ammi from the clinic, leaving my hair in a matted mess.

That was not a suitable time for the confession to be made for I had only recently discovered a stack of letters exchanged between my parents over the years during their marriage. These letters contained Ammi’s tirade over how she thought Father was unjust to her and had never actually loved her. The choice of words, however, were not those of a gullible and desolate woman but instead reflected the strength and composure that she was known for among her family and friends. In the letters, she addressed Father as ‘Mr. Thakur’ because in those days, a woman calling her husband by his first name was considered a mark of disregard. In a major part of the subcontinent, it still is.

For a fifteen year old who had just begun gathering her reasons and forming opinions about earthly affairs, I concluded that Father never really loved Ammi enough to braid her hair. It also occurred to me that he had exhibited the least concern for her when she first complained of those primitive stomach aches ten years ago. And, when she was finally diagnosed, the doctors declared she had only six months. Four months after the diagnosis, I was still unable to understand why she, who had led such a healthy life, should fall victim to cancer. Two months left, I thought, time was short. But now, I had the answer: It was because Father never loved Ammi. Father had been gone an hour, and I had started detangling the braided lumps in my hair while calculating the prospects of Ammi not getting cancer had Father loved her more when the doorbell rang. I opened the door and saw Ammi’s frail body leaning over Father’s. They were back from one of her routine chemotherapy sessions. He had one hand holding up her shoulder with his other arm braced around her waist.

I looked at her and thought how she had been the child of the mountains – calm, assertive and obstinate. For ten years while Father served for an armed government force securing the Indian borders, Ammi ran alone between doing the dishes, disciplining three children, fixing the broken bulbs, mending the dysfunctional basins, starting up a business, failing at it, working her job and attending meetings, never idle and always in haste.

But now her face hardly seemed her own for it held no hopes or dreams of the years no longer left to her. Her eyes that once mapped mountains were downcast. Her feet that ran her ahead of her contemporaries, could only shuffle, resisting movement. Father guided her patiently up the stairs in baby-steps until they reached the landing. When he settled her on the bed, I left the room and returned with a bowl of water and some hand wash. After wetting her hands, she suddenly shrieked, as though she had been stung. I stepped back.

“Ammi what is it?” I said.

“My hands. My hands.” She cried.

I grabbed them. “What about your hands?”

“They’re burning.” She opened her palms towards me exposing what looked like burnt skin peeling off her palm. I froze in horror. I took her hands and placed them onto mine.

“Let me see!” Father demanded.

“No, you’ll hurt her,” I said, holding onto them, fearful he’d crush her brittle hands in his ruthless ones. I had seen him hammer nails into wood with his fist, I had heard stories of him carrying massive logs of Sheesham across mountains to build Grandfather’s house. For a person unfamiliar with his savage capabilities, a staunch shake of his thick, calloused hand was enough of a testimony.

Over my protests, he seized her hands and ordered me to call the doctor. As I held for the doctor, I kept my eye on Father to ensure he didn’t hurt Ammi as he wiped her hands dry. But when I saw that a little massage from him caused her to calm down, I couldn’t believe my eyes. He then signaled me back her side and took the phone to speak with the doctor.

“Ammi you okay?” I enquired.

She gave a tiny nod, “I need to lay back.”

“Come here, I’ll help you.” I said, reaching carefully around her shoulder.

“No, call your Father,” she uttered. Annoyed and feeling thwarted, I called him over and retired to a corner of the room to observe him as he helped her recline. Over next few hours I watched as he fetched warm oil and massaged her comatose limbs until she fell asleep. He didn’t leave her side. But he doesn’t love you, I wanted to scream, and how could his rugged hands ever cause you enough peace to sleep? Haven’t you squandered countless nights of your life trumpeting how he never got you gifts because he didn’t believe in them? The one time that you insisted he buy you something as a token of ‘karwachauth’, all he returned with was a packet of ‘bindi!’ A packet of ‘bindi’ for having served him and his children all these years so assiduously. What cruel person does that? Even servants get garments on festivals..

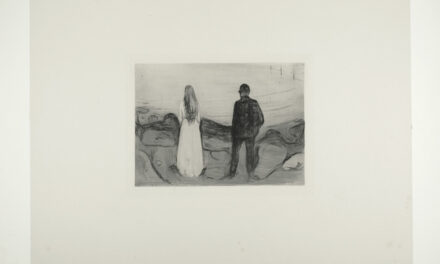

Ammi had been given away in an arranged marriage, so she should have known on the very night of her wedding that she had been tied to an indifferent man when he entered their room and retired to sleep without having uttered a word. He was always talking on subjects he thought of great consideration – the beauty of music, the honesty in a man, the triviality of death –Father could have belonged to a category of men who were poets, priests or mad men but he ended up a soldier, a married soldier. Perhaps that was where the problem started.

In the days that followed, he bathed, fed and walked Ammi as though she were an infant. But I knew that he only did so from a sense of duty, not from a feeling of love.

One morning, I was awakened by the incessant sputter of giggles. It seemed to come from the bathroom near two rooms at the far end of the house. I stood in the hallway and could see Father bathing Ammi and whistling along softly as he massaged her bald head. He was placing chunks of froth on her head and around her face as though trying to create a snowman out of her.

“No.” She insisted and timidly cleared the froth off her head.

“Wait.” He put it back.

“No.” She crinkled her eyes and pouted.

“Wait.” He tilted his head.

“No.” Her eyes glittered.

“Please, wait.”

I think she had smiled.

“See, you look beautiful.” He put it back on and the two burst into laughter. I squinted. But you don’t love her. You brought her a bindi on karwachautha.

Later that evening when Father did not show up for supper, I went looking for him. I found him sitting squat on a mat in a small area that Ammi had designated for daily prayers. My Father squatted offering prayers! I had never seen him bend down before the deity. Whenever Ammi would invite him to prayer, his answer had always been the same, “God resides in my heart, I converse with him there.” Finally, when Ammi grew weary of his reply, she stopped inviting him altogether. When he was done, he folded the mat and joined us.

“Can you bring me some plants?” Ammi asked as she ate. I eyed both of them consecutively. Father nodded. He’s going to forget it. How could he even comprehend what she asked for without making her repeat her request? Even if he does, he will definitely bring her the wrong plants.

But the next morning, I woke up to see Father tilling a narrow rectangular patch beside our house. The front yard was covered in concrete but he had removed a brick or two to expand a tiny muddy ditch. To my surprise, he had not merely bought Ammi some plants but he had bought the ones of the flowering species. Ammi loved them. She fixed and watered those tiny saplings to full grown plants. It was strange to see that with every flower that blossomed, her conviction to live also seemed to bloom. Whenever she came in from the yard, she would tell Father how her little garden was now full of flowers and of how hard she had worked for each one. Father, in turn, would reward her by cooking her favourite food.

Sometimes I would find them sitting out on the balcony sipping tea. They made jokes about her death and would break into cackling like little chipmunks. Suddenly, death did not seem to scare her. There is no sweeter miracle than seeing two people lose their worst fears. To this day, I cannot tell if it was god or love that breathed life into her but I know my Father had prayed and loved for over a thousand days and a thousand nights. I like to think that his devotion brought Ammi her life back, but the truth remains that love is a reciprocal occupation.

Four years later, he washed her of pus, blood and excreta with the same fortitude as the fire in which he would purify her body. He equalled a mother washing her new born for not a wrinkle folded upon his head in disgust.

***

After we returned home on the evening of performing Ammi’s last rites in the ancestral house, my Father began rummaging through a heap of photographs. He sat with his legs stretched out before him, enclosing the debris of color and black-and-white pictures as children might enclose castles of sand. He adjusted his new glasses to get a better look at each photograph as he carefully balanced them upon his thighs.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Looking for pictures,” he said sparing me but a short glance, “of your mother.”

He then proceeded to stick each photograph carefully into a photo album I hadn’t seen before. I realized that he must have bought it special, because it had been years since we had printed out photos, let alone buy new albums for them. When he was done, I went to him with a cup of oil.

“Papa, can you oil my hair, please?”

He put aside the photographs and album, removed his glasses and took the cup of oil from me. I squatted at his feet. He clutched me between his legs like a little sheep. He gently swept back my hair with his thick coarse hands and braided it after oiling to near perfection. I lay down on his legs and he petted me to sleep.

Neha Thakur studied in University of Delhi and graduated with Honours in English literature. Originally from Himachal Pradesh, India, she indulges in Hindi literature with equal vigour.